Windows to the world

Captain Rajiv Singh MNI takes a closer look into the one of the watchkeeper’s most important tools – the human eye

Seafarers are often told that the most important piece of equipment on the bridge is their own eyes. Like any piece of technology, you can only get the best use out of your eyes if you know something about how they work – and how to deal with their strengths and weaknesses. The sense we most rely on is sight. Approximately 80% of the information received by the brain is through our eyes and if there is ambiguity between the senses, the information collected by the eyes takes precedence.

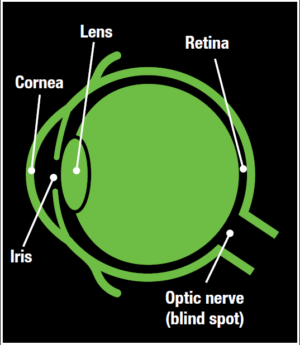

Our eyes are spherical in shape with a window-like structure that admits light into the eye while protecting it from outside elements. The retina at the back receives admitted light and converts it into electrical signals that are carried to the brain via the optic nerve.

Behind the cornea is the iris. This is the coloured part of the eye that controls the amount of light admitted into the eye, via the lens, by changing its shape and thereby adjusting the size of the pupil or aperture. The lens is flexible and changes its shape to ensure correct focus of objects seen on the retina.

The surface of retina is covered by light sensitive cells known as rods and cones. Cones sit behind the lens in the macula or fovea region of the retina and are responsible for colour vision and work in bright lights. The fovea region is the most sensitive area of the retina. Rods work well in dim light, are concentrated in the outer area of the retina and help with peripheral and night vision. Contained within the rods is rhodopsin (visual purple), a compound that helps the retina adapt to night vision. It typically takes about 30 to 45 minutes to reach its full concentration and can be broken down when struck by a bright light or glare. Beyond the fovea region is the junction of the optic nerve, which forms the blind spot.

Limitations of the eye

Night vision

Since it takes about 30 to 45 minutes for rhodopsin to reach its full density, at least 30 minutes should be allowed to ensure good night vision. Bright lights should be avoided before and during night-time watches. Fully dimmable lights should be the norm on a vessel’s bridge; some experts suggest red light for bridge lighting and torches. The instrument panel and displays should be switched over to night mode and their brightness adjusted to ensure optimal night vision – just bright enough to read the instruments clearly. One method which can help regain night vision when faced with unavoidable glare or bright lights is to close one eye.

During the day, excessive exposure to sunlight and glare should be avoided, as it increases the recovery time of rhodopsin to hours or even days. In fact, prolonged exposure to glare or the sun without proper eye protection can permanently damage the eyes. Wear good quality sunglasses (100% UV protection) to avoid glare and to protect the eyes against long-term permanent damage.

If you are on lookout duty, looking at an object directly is unhelpful because there are no rods in the centre of the retina. Motion is needed to attract our attention (especially at night) so lookouts must keep moving their eyes. This helps detect apparently stationary objects and avoids the image falling into an area with minimal rods or the blind spot.

Empty field myopia

When the environment is relatively unchanging and the eye has nothing to focus on, the lens takes up a position of rest. This can happen during very dark nights, in open seas and in hazy weather conditions. The focal distance under these circumstances is between 80cm and a few metres and the lookout may well be staring out and seeing nothing. This phenomenon is similar to when a digital camera covers its lens after a few minutes of inactivity.

Narrow field of vision

Though our eyes can usually accept light from an arc of nearly 200°, the field of vision to focus on a target is narrow – only 10 to 15°. We can perceive movement at the periphery, but cannot identify it. This can become tunnel vision.

Judging distance and blending into the background

A target that contrasts against the background, is apparently moving and is not in a glare is easier to see than a target in poor contrast, is apparently stationary and sits in glaring light. The absence of a background, context or reference point also makes it difficult for lookouts to judge distance. At night, lookouts must judge distance by size and brightness alone and this can be dangerous.

Perception and over-estimation of visual ability

The mind can play tricks on lookouts so that what they think they are seeing is different from reality. A faint white light with an occasionally sighted red light, fine on the starboard bow, could be perceived as a large vessel crossing at distance from starboard to port. In reality, it may be a small fishing vessel coming very close to the lookout’s own vessel.

Scanning the horizon

Considering all these vision limitations, there is no point in simply staring out into the open ocean or skimming the eyes across the ocean. Instead, lookouts should focus frequently on a distant object and then scan the horizon in blocks of about 15°. Observe each block for at least one second to detect objects. The distant object could be celestial, terrestrial or on the vessel itself – for example, the back scatter of the foremast light. Given that the movement of the eyeballs alone is ineffective, it is best to move the head continually to scan the periphery and create a complete picture at all times.

At night, vision is improved by looking slightly to one side of the object in focus. In addition to these visual scanning techniques, it is important to acquire the best situational awareness possible.

Want to know more?

This article is taken from The Nautical Institute’s book Human Performance and Limitation for Mariners, which aims to help seafarers understand their own limitations and abilities and build competency and confidence. Find it in our shop.

CHIRP Maritime has produced a fascinating – and free! – video on the working of the human eye and how to keep a better lookout. Vision and Decision can be found on YouTube at here.