202112 Tug order mix-up

As edited from TSB (Canada) report M19P0020

A container vessel was inbound to berth under pilotage in the early morning, in darkness and light winds. Two tugs were secured fore and aft on the port side well before arrival. As a memory aid, the pilot had the tugs positioned alphabetically along the vessel’s port side, securing ‘F’ tug forward and ‘H’ tug aft. The pilot was conning the vessel from the starboard side of the bridge and was gradually reducing speed.

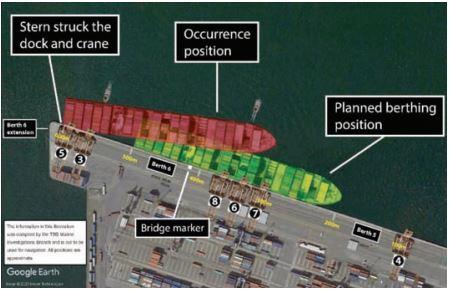

The approach to the berth was as expected for a very large and wide vessel; nearly parallel to the dock at about 10 metres off with a speed of approximately 1.3 knots. There were no significant effects from the ebb tide. With approximately 200 metres to advance, the pilot ordered the engines dead slow astern in order to reduce speed to less than one knot.

In anticipation of the stern moving towards the berth due to the astern engine order, the pilot in error requested ‘F’ tug (forward) to back up on the line and take up the strain. As tension came on the line, the vessel’s stern started moving towards the berth. The pilot ordered ‘F’ tug to increase power to maximum and ‘H’ tug (aft) to push maximum. This error in tug orders resulted in the vessel’s stern pivoting rapidly toward the berth, the exact opposite of the intended action.

The Master attempted to alert the pilot to what was going on. At the same time, the pilot ordered the bow thrusters full to starboard, the engines dead slow ahead, and the helm hard to starboard. However, with the tugs still operating at maximum power in the wrong direction there could be no stopping the pivot. With the vessel now at an angle of about 10 degrees with the berth, the flared stern struck the quay and made contact with one of the shore cranes which collapsed inwards toward the terminal, the boom falling onto the vessel.

Although ultimately the allision was caused by human error, the investigation also found that there has been an increase in the size of container vessels berthing at the port over the last decade, and no corresponding upgrades to the terminal such as more appropriate fenders.

Lessons learned

- If effective bridge resource management (BRM) is not maintained by bridge teams, including pilots and tug Masters, there is a risk that errors will go uncorrected and cause unwanted consequences.

- Some port infrastructure has not kept up with increases in vessel size and mariners should be aware of these inconsistencies.