Work, rest and port calls

A fundamental skill for any navigator is the ability to maintain situational awareness and make good decisions, both in planning and in carrying out the voyage. That requires good training, and good maintenance and development of knowledge. It also needs sufficient physical and mental rest

Seafarers rightly take pride in their resilience and ability to do the job that needs doing. Unfortunately, one of the symptoms of fatigue is that it prevents you from realising when you are unable to carry on safely.

Dr Michelle Grech explains further in The Nautical Institute’s publication Human Performance and Limitation for Mariners: “Fatigue makes it harder to concentrate and pay attention, reaction time is slower and co-ordination is poorer. In most cases, fatigue leads to slower, more narrowed and muddled thinking, affecting decision-making and judgment.

“Crucially, fatigue reduces the ability to recognise when your performance is impaired. Individuals suffering from chronic fatigue are the worst judges of how well they are performing. As a result, a large number of seafarers may continue to work, even conducting safety-critical tasks, under the influence of fatigue, not realising that their performance and judgement is impaired.”

It is precisely because you might not realise that there is a problem that it is so important to keep accurate records of your own work and rest hours – and comply with the onboard fatigue risk management system. A recent survey by the World Maritime University found that 64% of respondents reported adjusting their work/rest records to show they had worked fewer hours than was actually the case.

Concealing the problem may put you and your ship at risk – and in the long run, makes it harder to solve at source if those with the power to change the system believe the current situation is working.

Workload, compliance and safety

The maritime industry recognises the importance of rest for good performance and health. Attempts have been made to manage the workload, including updating minimum requirements in the 2010 Manila Amendments to the STCW Code, which came into force in 2012. This mandates a minimum of 10 hours’ rest in any 24-hour period and 77 hours in any seven-day period. Periods of rest may be divided into no more than two periods, one of which shall be at least six hours in length, with no more than 14 hours between periods of rest. These hours must be logged and can be checked by any Port State Control or flag surveyor.

Work ‘as imagined’ and ‘as done’

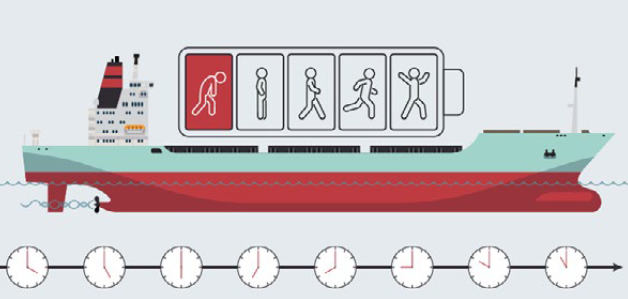

This all looks great on paper. However, the work/rest requirements do not take into account current knowledge on sleep, fatigue and the science of safety. Part of the issue is that there is a huge difference between work ‘as imagined’ – the obvious things that have to be done – and work ‘as done’ – the invisible background work that goes into making the obvious work possible.

As Intermanager’s Captain Garry Hallet explains, writing in Seaways about port calls: “The ‘work as imagined’, is that the ship arrives in port, loads or unloads its cargo and then sails on to the next port and repeats. On occasion, the charterer may wish to fuel the ship but that’s about it.

“The ‘work as done’ is usually very different. Stores are loaded; garbage discharged; slops disposed of; lubricants and fresh water taken; service engineers arrive to upgrade systems or fix issues on board, crews change; port inspectors and flag and class surveyors come and go. On top of this additional workload, there are company inspections, reviews of the ship’s safety management system – and so the list goes on.” Then, of course, once you’re back at sea, the watch system continues, even if your rest time was disturbed, or not possible at all.

What it looks like at sea

Port calls are just one example where the work needing to be done may exceed the time allotted to do it. The Nautical Institute asked members of its Seagoing Correspondence Group – who are all currently at sea – to share their experiences. They make it clear that being on watch, or even conducting operations during port calls, are far from the only responsibilities that seafarers face, and that the level of workload is causing fatigue – and putting safety at risk:

“Fatigue, excessive paperwork and complex SMS continue to be the key challenges [mariners] are facing at sea. The workload has increased many times, and manning is an issue which the ship owners are not addressing.”

A Second Officer responsible for voyage planning goes into more detail: “To give just one example, at the commencement of a sea passage, the vessel is required to report all events and send detailed data to the owner, the charterer, the sub-charterer and a second sub-charterer. […] All of this has to be completed immediately after completing discharge and sailing from port, after less than 24 hours alongside.

“Each recipient probably believes that their report is simple and takes only a few minutes to complete. In reality, for the crew it means additional hours of work, often distracting officers from their watchkeeping duties. However, the problem is mainly visible only on board the ship.”

Solving the problem at source

While accurately reporting and managing your own fatigue level is important, the disconnect between real and expected workload is an issue that must be solved at a higher level. The Nautical Institute is working to make sure that the problem is visible beyond the ship, to shipowners, charterers and, above all, to the IMO flag state representatives who create the legislation.

We are working with flag states to ask the IMO to review the effectiveness of the current legislation, identify and confirm issues with the current system. We must then move to identifying solutions, which may involve changes to minimum crewing levels, for example.

Individual responsibility is important, but it is making sure that seafarers are heard and respected at the highest level that will make a difference long term.