Taking action

Far from being a theoretical concern, recent incidents in geopolitical conflict zones have underscored the very real and immediate dangers posed by compromised global navigational satellite systems (GNSS).

Dealing with disruption – and coping with compromise

Gard P&I Club explain why it is imperative that we recognise the signs of GNSS disruption and understand what to do when we come across them.

Onboard systems like ECDIS, Radar/ARPA, Gyro compass, course recorder, and the autopilot are all heavily reliant on GNSS feed. This means they are highly likely to be impacted by any disruption to the signal. Mariners must maintain heightened attention and awareness for signs of GNSS disruption when using them.

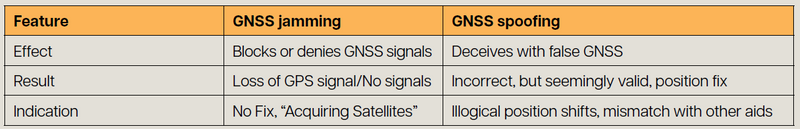

Depending on whether the disruption is caused by jamming or spoofing, tell-tale signs can vary from clear audible or visual alarms to no alarms at all.

GNSS jamming is the act of blocking or interfering with legitimate GNSS signals by overwhelming them with stronger, unauthorised radio signals. Think of it as trying to have a conversation in a very noisy room – the noise makes it impossible to hear what the other person is saying. GNSS spoofing is the act of transmitting false GNSS signals designed to deceive a receiver into calculating an incorrect position, velocity or time. Instead of blocking the signal, a spoofer imitates a legitimate GNSS signal, making the vessel’s receiver believe it’s real. The GNSS display will show a position, but it will be inaccurate, potentially by a significant margin. Derived speed and course information will also be incorrect. A table showing a summary of key differences can be found below:

While specific indications for GNSS disruption can vary between equipment and manufacturers, examples shared by Anglo-Eastern’s Maritime Training Center, Delhi, India, highlight several key signs that mariners can watch out for:

- Unusually high HDOP (Horizontal Dilution of Provision) values, eg, greater than ‘4’ indicating unreliable accuracy,

- RAIM (Receiver Autonomous Integrity Monitoring) alerts entering caution or unsafe modes, and

- Elevated Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) values.

On ECDIS, jamming can trigger sensor failure alarms, potentially leading to a switch to backup sensors or dead reckoning. Jamming may even freeze the chart display altogether if no secondary source is defined. Conversely, spoofing presents a more deceptive threat as the GNSS receiver might report an incorrect but seemingly valid position, often without RAIM detection.

In such spoofing scenarios, ECDIS can display incorrect positions, and Radar/ARPA systems, when GNSS-fed, will show incorrect data. Gyro compasses may also enter an alarm state if relying on GNSS for drift stabilisation. Your equipment manufacturer should be able to provide further advice on how GNSS denial will show up on your own bridge equipment.

Alarm fatigue and sensory overload

Alarm fatigue is a significant challenge during GNSS signal loss. The disruption or loss of GNSS signal often triggers numerous simultaneous alarms across the bridge, leading to a sensory overload that can be both disconcerting and distracting. Effectively managing these alarms and prioritising critical information is essential to maintain situational awareness and ensure safe navigation.

Beyond the bell: covert GNSS failures

Situations can also occur where no alarms are triggered, making detection much harder. For example, the Australian Transport Safety Bureau reviewed a near-grounding incident involving a vessel navigating the Great Barrier Reef. In this case, a malfunctioning GPS unit (due to an antenna fault) fed incorrect positional data to the ECDIS, Radars and other bridge equipment. As the ship’s position was not being monitored through other means and no alarms were activated, the inaccurate GNSS data and vessel’s deviation from its planned course went unnoticed by the crew, pilot and even Vessel Traffic Services (VTS).

While not directly linked to jamming or spoofing, cases like this one underscore the dangers of unaddressed GNSS anomalies, whether from technical faults or external interference. They highlight the inherent risks of relying solely on a sole source of navigational data, even when it appears functional, and emphasise the importance of crew training in recognising and responding to these events.

Responding to GNSS disruption

Once a GNSS interference alarm is triggered, mariners must identify its root cause instead of simply silencing or deactivating it. You should call the Master immediately. The vessel should have a plan in place for actions to take if GNSS signal is lost; make sure you are familiar with it before it becomes crucial. The measures you will need to take will vary from ship to ship.

Key strategies include a secondary receiver (if available), employing parallel indexing, utilising Radar overlay on ECDIS and manual position plotting on ECDIS.

While manual position plotting by range and bearing is possible near conspicuous landmarks, it may not be feasible when a vessel is further away from land, navigating a flat coastline or is in an area that lacks discernible objects.

Operational decisions

Beyond any technical measures required, the Master will also need to take vital operational decisions.

They may need to consider:

- Reducing speed, which not only allows more time for assessment but also significantly lessens potential damage during an incident like grounding,

- Increasing bridge resources, and

- Making an informed decision on whether to proceed with the voyage.

These critical decisions should be guided by a comprehensive set of considerations that are ideally integrated into the vessel’s GNSS disruption response plan.

Such factors include:

- The complexity of the passage,

- Available room to manoeuvre,

- The availability and capability of pilots or local tugs for assistance,

- The reliability of buoys and fairway markings,

- The presence of safe anchoring points along the route,

- The density of traffic,

- Effectiveness of Vessel Traffic Service (VTS) management,

- General visibility, and

- The geographic extent of the GNSS disruption.

Should the vessel stop?

Vessels, of course, do not navigate by GNSS alone. While GNSS has undoubtedly enhanced navigation safety, ships have successfully sailed without it for centuries. However, the simple fact is that GNSS disruptions will often have an adverse impact on the operation of a vessel. This might mean speed reductions, deviation from the intended route, or even the interruption/suspension of the voyage.

All suspected GNSS disruptions should be reported to the relevant authorities and organisations to aid wider situational awareness and warnings.