201852 Weak planning and BRM breakdown leads to grounding

Weak planning and BRM breakdown leads to grounding

As edited from official UK Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) report 23/2017

At one point the lead pilot received a call to his mobile telephone from the pilot on an outbound vessel to discuss how and where they would execute the meeting manoeuvre between the two vessels. Both pilots agreed to a conventional port to port meeting, with the speed of the container ship being adjusted to ensure the meeting took place to the east of the precautionary area, a place in the channel where a large turn to starboard was required.

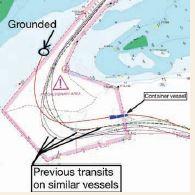

The container vessel was now making 12kt and the lead pilot informed the Master of his planned manoeuvre into the precautionary area in order to make a turn first to port to allow for more sea room and then to large starboard. To combat the strong flood tide and prevailing headwind, the lead pilot stated that he intended to navigate the vessel ‘deep’ into the precautionary area before beginning the starboard turn.

The lead pilot gave the helmsman a series of courses to steer that, over the next four minutes, brought the vessel on to a heading of 260°. Shortly afterwards, the lead pilot ordered the starboard turn and the engine set to full ahead. Soon, he expressed concern to the assistant pilot about the turn. At the same time, the Master expressed similar concern to the OOW in his native language, Romanian.

Soon after, the container vessel grounded with the engine at full ahead. The Master implemented the vessel’s emergency procedures. The crew’s initial inspections and tank soundings indicated that the vessel’s hull had not been breached. Tugs quickly freed the vessel on the rising tide.

Some of the report’s findings include:

- The intended route through the precautionary area was not charted, and key decision points, wheelover points and abort options were not identified.

- The absence of a charted pilotage plan meant that the Master, his bridge team and the assistant pilot were unable to monitor the lead pilot’s actions and the vessel’s progress during the execution of the turn in the precautionary area.

- The lack of a shared understanding of the pilot’s intentions prevented the bridge team from providing the support to challenge or seek to clarify the pilot’s actions.

- The bridge team became disengaged from the pilotage process and allowed the lead pilot to become an isolated decision-maker and a single point of failure.

Lessons learned

- If you have concerns about the conduct of the vessel, discuss them with the entire bridge team.

- For critical turns or other manoeuvres, have key decision points established in advance. In this case, when compared with past trips, the vessel was obviously too far north as it entered the precautionary area and prior to making the starboard turn. This should have triggered an abort decision.

Editor’s note: The report also states: ‘It is accepted that detailed plans for complex pilotages cannot always be produced by navigating officers and ports prior to a vessel’s arrival at a pilotage station, and that vessels often need to deviate from planned tracks in busy and congested waters. However, realistic intended tracks need to be plotted and key decision points identified.’

This basic premise has been identified by other investigative agencies. In Canada, for example, the Transportation Safety Board published a recommendation with similar ideals in 1994.