Free Article: Sharing user experience for better design

Bad design is making equipment inefficient, unsafe – and, ultimately, expensive. Could HCD be a way to improve the process, asks Captain Aly Elsayed AFNI

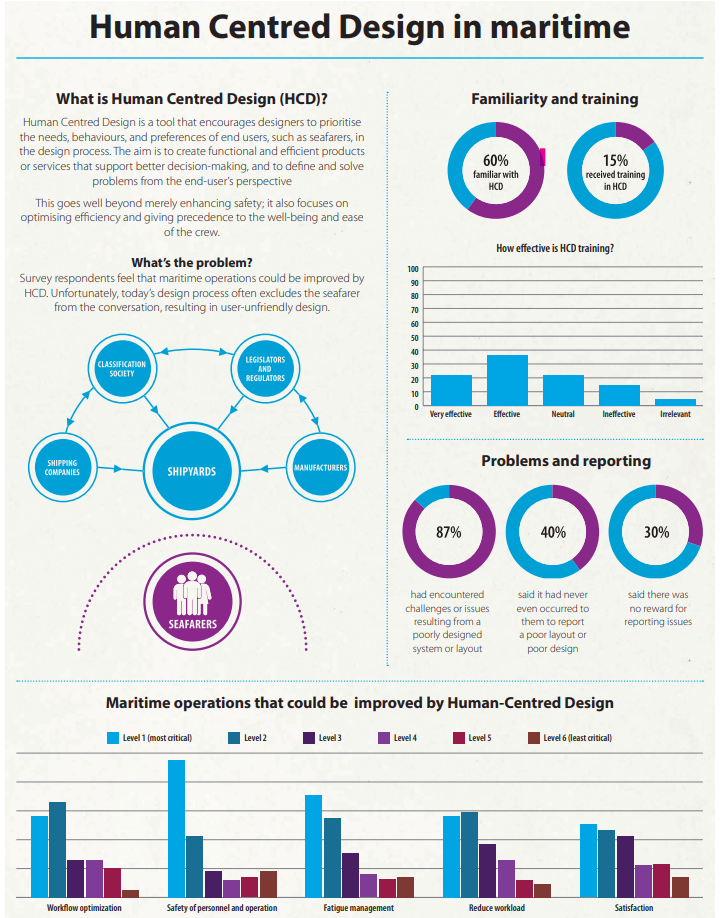

A survey conducted by The Nautical Institute in collaboration with the OCEAN Project suggests that the industry is approaching training in Human Centred Design from the wrong angle. Changing the way we approach this might give seafarers more of a voice to express the issues they face at sea – and could go some way to alleviating problems with poor design. The survey began by asking respondents how familiar they were with the basic principles of ergonomics and Human Centred Design, and whether they had received any training in the area. A follow-up question asked participants whether they had found this training useful and effective.

Of those currently working at sea, just over half – 56% – were very familiar or somewhat familiar with the concept of HCD in the maritime industry. Just 9% had received any formal training in this area. However, responses from those who had received this training were overwhelmingly positive, with 91% saying it was either effective or very effective. The overall survey response appeared broadly similar, with 60% of respondents either familiar or somewhat familiar with the concept. Levels of training were slightly better, with 15% having formal training in this area. However, opinions on the effectiveness of this training were split, with just 59% percent finding it effective to some extent.

The data suggests that training in ergonomics is something that it is more likely to happen in shore based professions – if it happens at all. But it appears that it could have a much greater impact if it took place while seafarers were still at sea.

What should be changed?

Neither lack of formal training nor lack of familiarity with the general concepts prevented seafarers from identifying problems with the setups with which they were working. 87% of mariners said they had encountered challenges or issues resulting from a poorly designed system or layout.

Asked to elaborate, the list of complaints or places where they had found design user-unfriendly or in need of improvement was long and varied. Some items came up time and again – ECDIS was a frequent culprit here – while others were specific to certain ship types and operations.

Just a few examples:

- Having to run across the entire bridge to answer a phone or radio. Helm controls, telegraph, radar and ECDIS widely dispersed

- Too many bridge alarms, which cannot be easily told apart

- Having to stand on the table to operate valves or searchlight

- Vital instrumentation not visible to helmsman and/or navigating officer

- Difficulty avoiding danger zones during mooring

- Bridge windows which obscure or distort the view Even where changes were made to existing vessels, user input was not necessarily sought before those changes were made, and sometimes they introduced new problems.

Why aren’t these problems reported?

Around half of respondents said it had never even occurred to them to report a poor layout or poor design. 40% of seafarers fell into this group. Overall, seafarers were the most likely to say that doing so would only create more hassle and paperwork. Consistently across all groups surveyed, about 30% said there was no reward for reporting issues, and around 35-40% commented that seafarers were good at coping with difficult circumstances. While true, this clearly does little to improve matters. “To our detriment, we make it work,” one noted. A further 40% noted that layout and systems were in the hands of the classification societies, and they could have little influence.

Invited to comment in more detail, respondents highlighted that cost was often a concern over crew well-being, that it was difficult to know who to report to, or that reports had been ignored, rejected or actively discouraged. Some were afraid of reprisals or being labelled as a troublemaker.

If we are to move from a cost-centric model to a human-centric design model, we need not only to communicate what changes are needed, but also to emphasise the benefits that this will bring to all stakeholders, from bridge to boardroom, in terms of increased safety and better efficiency. “Instead of putting money in the first place, one should consider the benefits of investing in their seafarers in the long run,” one respondent commented.

The disconnect

Just 25% of those at sea said that users were actively or occasionally involved in the design, development and newbuilding process in their company. Even this was optimistic compared with the overall view, where just 20% saw some degree of user involvement – in other words, 80% did not see any evidence of user involvement when creating a design. Six per cent said that users are actively engaged from the initial stages, and another 15% that they were involved at certain points, but not consistently throughout the entire design, development and new building process.

There are many barriers between the seafarers/users and the designers. The initial point of contact to give feedback is between the seafarer and the shipowning/ management company – who may not even be their employer. There are many stakeholders playing a role in the design process, including shipowners, classification societies, those who write the regulations, the shipyards themselves – and the whole process often governed by cost as well as safety. Too often, the users voice is not heard at all. The proof, if proof was needed, can be seen in cases where design has been altered not in response to warnings that poor design was causing an issue, but only after that issue had actually led to an incident, as in the case of the City of Rotterdam.

What can be done to bridge this gap?

- Many survey respondents commented on the importance of actively involving seafarers in the design process, with suggestions including

- Making reporting easier through having QR codes on equipment

- Having a ‘build Captain’ with seafaring experience as part of the design team

- Having a board of actively employed crewmembers sought after by the yards to improve their designs

- Design teams to visit every group of users (NOT THE MANAGERS!) [sic]

There was also concern that proper concern for safe use should be built in from the beginning of the process, and it should not be on those at the sharp end to report problems after the fact. Several commenters felt that that legislation mandating user involvement from the start of the process is the only way to ensure this.

Will more training help?

Respondents certainly seemed to think so. Eighty percent of respondents said that enhancing awareness and training about HCD approaches and ergonomics would have a significant impact on seafarers’ satisfaction and decision-making, increasing to 95% of those at sea.

Among other things, providing this training would help create a shared language between designer and user, potentially allowing a more effective sharing of ideas. Training in maritime HCD in particular would help designers know what sort of questions they should be asking, and what issues they should be aware of.

We still have a massive amount of work to do to close the gap between end user and designer, but creating a shared language and making both sides aware of the channels through which they can communicate is a start.

A video produced by the NI, also based on this research and looking into HCD in more detail, is currently in development