Communication and VTS - Share the message

Jillian Carson-Jackson FNI FRIN examines the processes behind effective communications between vessels and VTS.

Research and experience suggest that a key factor in many shipping accidents is a breakdown in communication. This includes communication within the bridge team, between different areas of the vessel and between the vessel and an external party, such as VTS. Sometimes the breakdown in communication can be due to language difficulties, technology issues or even differences in cultural references.

What is communication?

To communicate is to exchange information, by speaking, writing or some other means. In VTS there are different aspects to communication:

- Internal – within the VTS centre;

- External – between VTS and ships, as well as between VTS and allied services.

There are also different methods which can be used for communication. VHF radio is a key way to communicate with VTS, however, there are a number of others, including phone, e-mail and through AIS. In VTS, information is critical. A core duty of VTS is to collect, analyse and provide information. To do this effectively, structured communication is required from both the sender and the receiver.

Creating a traffic image

Each VTS centre maintains a traffic image. To do this, VTS needs to have information on the vessels in the area. The only way to do this is through communications from and to the vessel. To do this, VTS uses:

- Radar (which doesn’t require the vessel to ‘do’ anything)

- AIS (the vessel is required to have a working AIS unit transmitting the correct information)

- VHF radio voice reports In addition, the VTS can have an idea of where a vessel is ‘supposed’ to be through the VTS sailing plan.

The traffic image that VTS maintains is only as good as the information it receives: it is the old story of ‘garbage in = garbage out’. If the information transmitted isn’t correct, then the VTS will have a flawed traffic image – there will be a breakdown in communication. Alternatively, if the information is accurate, the VTS will have a much more accurate traffic image.

Communicating with VTS

In order to communicate, someone must send a message that includes intentions (what the sender means), which are coded in some manner (words, text, images, etc.) and sent in some way to the receiver. The receiver must then decode the message and make sense of the meaning.

At each stage of communication something can go wrong. The intention may be miscoded – have you ever said one thing, but really meant something else entirely? The transmission method for the message may be flawed. Think about a time when you tried to listen to a radio station that was a bit too far away, or when you tried to Skype with someone over a poor internet connection. The means to decode the message may not be compatible with the way the message was encoded. A classic example is the speaker mispronuncing a word in a second or third language that you then just can’t make out.

It is advised that a maximum of two message markers and two phrases are used in one transmission to avoid an overload on the recipient.

Using feedback is critical to understanding in such circumstances. Communication doesn’t occur in isolation, and there is a backdrop of existing relationships, background noise and your own ‘readiness’ to receive the message. The diagram opposite is a visual representation of the process of communicating.

Message Markers

The issues around communication exist in all languages. English has been identified as the language to use at sea, but many mariners speak English as a second or third language. Recognising this, the IMO has developed a set of Standard Marine Communication Phrases (SMCP) to help standardise and simplify communication. These include a few key phrases that specifically refer to VTS. In addition, SMCP includes a series of ‘Message Markers’, or single words that help focus the message. Message markers may be linked with other key words, such as ‘Weather INFORMATION’ or ‘Collision WARNING’. Message markers used by VTS are:

- Information

- Warning

- Advice

- Instruction

- Question

- Answer

- Request

- Intention (usually used by a ship not VTS).

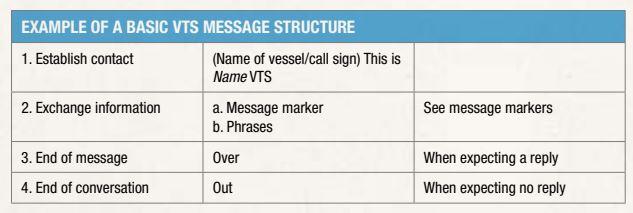

Message Structure The way in which a message is structured can help when it comes to decoding it. A consistent message structure is normally more readily understood, no matter how it is transmitted. There are several steps that can help structure a message to or from VTS effectively:

- Using standard radio procedure when establishing contact Making effective use of message markers

- Choosing the appropriate phrase or simple text

- Ending the message correctly.

The table above presents a sample, basic, message structure for VHF communication with VTS. It is followed by two typical conversations using this structure.

Sending the message

Having looked at the process of communication, the language used and the structure of the message, how should you prepare and transmit a message on VHF radio, phone, or even in person? Here are six key points to follow:

Prepare – write the message down and practise saying it out loud before actually transmitting it. When preparing to send on VHF, take a moment to listen to the frequency and make sure it is free. Only start your message when you are physically and mentally ready.

Tone and Volume – the tone and volume you use when you communicate are just as important as the words that are used. Always remain calm, professional and polite.

Emphasis – what is the focus of the message? VTS operators are taught to emphasise the message markers and key words for further clarity. For example: ‘WARNING, SHALLOW water AHEAD of you.’

Speed – the average adult with English as a first language speaks at a speed of between 150 and 190 words per minute. For someone who doesn’t speak English as a first language this is way too fast! It is recommended to speak at about 120 words per minute. In emergency situations this should be even slower.

Group and Pause – group words into phrases and add pauses between groups. When you put in pauses on purpose you reduce the likelihood of using fillers such as ‘um, hm, uh, er …’. If you are having a hard time deciding how to group your phrases, a simple rule is to put a pause after every four or five words.

Repeat – when you have a key point in a message, you can repeat it and let people know by saying, ‘(I) repeat’. Repetition is also useful when there is difficulty somewhere in the communication process.

Receiving the message

When you receive a message, there are some handy tips that can help make sure subsequent communications are effective – both for the ship and the VTSO. Three key points will help you ensure you receive the message correctly:

Listen – really ‘listen’ and don’t interrupt

Clarify – ask questions if you don’t understand

Understand – identify the main issues and repeat that back to the sender.

Do not assume what the sender will say, particularly when receiving routine communications. When you put it all together, you get clear, concise and purposeful communication.

BROADCAST OF NAVIGATION INFORMATION:

All Stations (x3)

This is Anyport VTS (x3)

Navigation INFORMATION

Anyport buoy #4 reported 4 cables south of charted position

Anyport VTS

Out

BROADCAST OF NAVIGATION INFORMATION:

Anyship (x2)

This is Anyport VTS (x2)

INFORMATION

Tanker Alpha1 outbound, approach calling in point 3, followed by Ferry Bravo2

Dredging operations in the vicinity of berth Charlie, REQUEST pass slow speed, no wake

Anyport VTS

Over