202459 Procedural dysfunctions and fatigue contribute to undocking accident

As edited from MAIB (UK) report 6/2024

A tanker had berthed at jetty 1 for partial unloading. There was a weak flood tide and the vessel did not use tugs. The arrival pilot discussed tug use for the vessel’s departure and informed the Master that use of a tug was mandatory for vessels departing jetty 1 on an ebb tide. The pilot also made a note in the pilotage database that the vessel had weak astern power.

Unloading proceeded normally and a departure was planned for the next day. A tug was initially booked for a 05:00 departure, but about seven hours before departure the duty pilot (not the same pilot as on arrival) called the port and highlighted some concerns about the height of tide at 05:00. The pilot asked if the tanker could instead sail at 04:00, when tidal currents would be somewhat less and the height of tide would be 1.19m higher than at 05:00, but there would be no tug available. This was agreed between the pilot and the port. The agent informed the tanker’s Master that departure was now confirmed for 04:00 without a tug.

At 03:40, the pilot arrived on board and discussed the departure with the Master. He had not accessed the pilotage database to review the note entered there by the arrival pilot. With the vessel’s bow in the direction of the full ebb stream, the pilot’s plan was to let go all lines except a spring and then swing the vessel’s stern 90 degrees to the berth before letting go the spring and going astern. The pilot reiterated the need to stay clear of the shoal water to the south-west of jetty 1 and the tanker’s Master confirmed the vessel’s maximum draught as 7.4m aft.

The pilot then discussed the fact that the departure had been brought forward one hour because of his concerns about the falling tide. The Master asked the pilot to check if a tug could be obtained for a 03:45 departure. Port authorities confirmed that no tug was available but the Master remained concerned about the lack of a tug, despite the pilot’s reassurances. During this exchange the pilot talked through the plan to use the forward spring to control the turn off the jetty and asked that the anchor be kept on standby.

Further discussions took place between pilot and the Master about the use of fenders, transit marks and the manoeuvre off the jetty. At 03:54, the pilot used the radio to brief the line handlers about the plan for departure. Discussion about the manoeuvre off the berth then continued between the pilot and the Master. The pilot was concerned that preparations for sailing were behind schedule. At 04:00, the Master, speaking in a language not understood by the pilot, instructed mooring parties not to release the mooring lines. Then, the pilot reiterated the steadily reducing height of tide to the Master.

At 04:05, the Master called the ship’s agent to highlight concerns about sailing without a tug. This call became a heated three-way conversation between the agent, the Master and the pilot, and ended with the pilot saying that 05:00 was too late to conduct a safe departure. A few minutes later, acquiescing to the pilot’s pressure, the Master ordered the ship’s lines to be singled up.

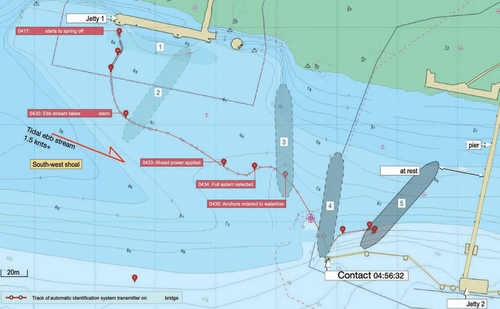

Soon, all lines other than the forward spring had been let go. The pilot then manoeuvred the vessel off the berth and, at 04:23, the order was given to slip all lines. The forward spring snagged briefly but was quickly cleared and the pilot continued to manoeuvre the vessel to bring it to 90 degrees with the berth. At one point the pilot ordered the Master to stop the engine and then go ahead. The tanker was going astern and then the pilot requested dead slow astern and then slow astern. About nine minutes after slipping the lines, the ebbing tidal stream of about 1.5 knots was taking the vessel bodily towards the westernmost dolphin of jetty 2.

About one minute later, the pilot attempted a kick to starboard by ordering ahead power and full starboard rudder. Then, the pilot ordered the engine to full astern. Meanwhile, the duty VTS officer observed on radar that the vessel was nearing jetty 2 and called twice in quick succession to check if all was okay; but the calls were not heard on the bridge.

Starting at 04:35, and for the next 90 seconds, the Master and the pilot both shouted a series of orders about the anchors. At the end of this it was stated that the anchors were just to be lowered to the waterline.

The pilot again ordered ‘Hard starboard, kick ahead, kick ahead’. Twelve seconds later, the tanker’s starboard aft quarter collided with the westernmost dolphin of jetty 2. With the engine now full ahead and the wheel hard to starboard, the vessel scraped along the dolphin. Soon, both anchors were down and the engine was set to stop. The vessel’s stern cleared the westernmost dolphin, but as the bows pushed into the soft mud of the riverbank the stern hit the walkway on jetty 2, dislodging a section of the jetty. The vessel was now stuck, the vessel’s bows partly held by the anchors lying to port and by the mud of the riverbank. The vessel’s bows were approximately 48m away from the pier of jetty 2 and the stern was resting on the jetty. Some time later, the tanker was re-berthed with the assistance of two tugs

The investigation analysis and findings shed light on certain contributing factors, among others things:

- The pilot was probably fatigued when boarding the tanker and during the departure manoeuvre. Judgement and reaction time are adversely affected by fatigue.

- The pilot had not visited jetty 1 for more than four years so he had not encountered the new extension to jetty 2. He was therefore unfamiliar with how much this new berth extension constrained the available navigable water, especially for a departure when docked in the easterly direction with a strong ebb tide.

- The pilot was not informed of the mandatory tug requirement for such ebb tide departures from jetty 1. He was not alone in this lack of local knowledge; the port controller and the VTS officer on duty at the time of the accident were also unaware of the requirement. This was a recently implanted risk mitigation measure that had been poorly disseminated to persons of interest.

Lessons learned

- In this instance we can observe the near total collapse of Bridge Resource Management (BRM). On the one hand, the pilot was not properly supported in the manoeuvre by the bridge team. No one was assigned specific tasks. On the other hand, the Master, notwithstanding his misgivings about not employing a tug, acquiesced to the pilot’s misinformed judgement, although the pilot’s abilities were undermined by fatigue. Lesson for Masters – trust your experience, and delay departure if you have doubts.

- Incredibly, neither the pilot, the port duty officer, the VTS officer, nor the agent knew that an east-facing vessel in an ebb tide was required to have tug assistance for departure. How could we expect the Master to know? However, given the very restricted waters and strong ebb tide, normal seaman-like precautions would have dictated the presence of a tug.

Experiences a marine accident or near miss? Help keep others safe by sharing what you learnt from the incident

Contact us in confidence at [email protected]