202008 Grounding was not in the plan

Edited from official TAIC (New Zealand) report MO-2018-203

A container ship picked up a pilot while inbound to a port in darkness. The Master, OOW and helmsman were on the bridge. The pilot showed the bridge team the planned route on his portable pilot unit (PPU). The ship’s passage plan was displayed on the vessel’s ECDIS. It was similar to the pilot’s route in that the ship was to stay in the centre of the narrow channel, but there were subtle differences in the radius of the turns.

Soon after the inbound trip began, the pilot checked the settings on the PPU and found an unwanted 18-metre offset to starboard. He was unable to remove the offset, so decided to stop using the PPU to monitor the ship’s progress and instead con the ship visually, using the ship’s radar as an aid. He did not tell the rest of the bridge team that he had stopped using the PPU. Soon, harbour tugs were in attendance and secured fore and aft.

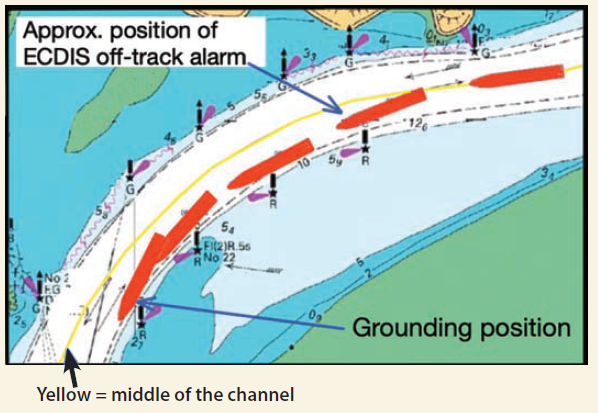

By this point, the ship was already to port of the planned track. Despite this, the pilot gave a succession of large helm orders to port (between 20° and 35° rudder angle). As the vessel responded to the port rudder, the deviation to the left of the planned track increased, activating the off-track alert on the ECDIS. The alarm was acknowledged but the information was not passed on to the other members of the bridge team.

The vessel gradually slowed as it made the turn to port, deviating ever further to the left side of the channel. Now, at a speed of 2.5 knots, the bridge team felt the ship heel over to starboard. At that point the Master asked the pilot why the engine was still on dead slow ahead. The pilot ordered the engines to increase to slow ahead. However, the ship continued to lose speed and soon stopped altogether. The bridge team now realised the vessel was aground. With the help of the tugs and the vessel’s engine the container ship

was brought off the bank and back into the channel, continuing the voyage to the berth without further incident.

The official investigation found that, among other things, the grounding demonstrated why it is not always appropriate to use visual navigation exclusively when manoeuvring large ships in narrow channels, especially at night. The accuracy of electronic navigation aids such as PPUs and ECDIS could have added value; the ship’s departure from the intended track would have been readily apparent in time to avoid the grounding.

Lessons learned

- The real-time instantaneous position information given by ECDIS and PPU equipment should always be put to good use in restricted pilotage waters, particularly when in darkness.

- When under pilotage, don’t leave your BRM techniques in the classroom. Challenge the pilot if there is divergence from the planned route.

- In order to raise a challenge if need be, you have to know the plan and follow its execution.