201666 Wrong helm applied and vessel grounds

Edited from official Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) report M14C0219

A small tanker was making way in restricted waters and in darkness, proceeding full ahead at speeds sometimes greater than 19 knots (SOG) as a result of a following tidal current close to 3 or 4 knots. The officer of the watch monitored the vessel using the starboard radar and the ECS, and the Master was on the bridge. The vessel was approximately 2.6nm from the next course change of 071°T, through a channel that is 0.3nm at its narrowest.

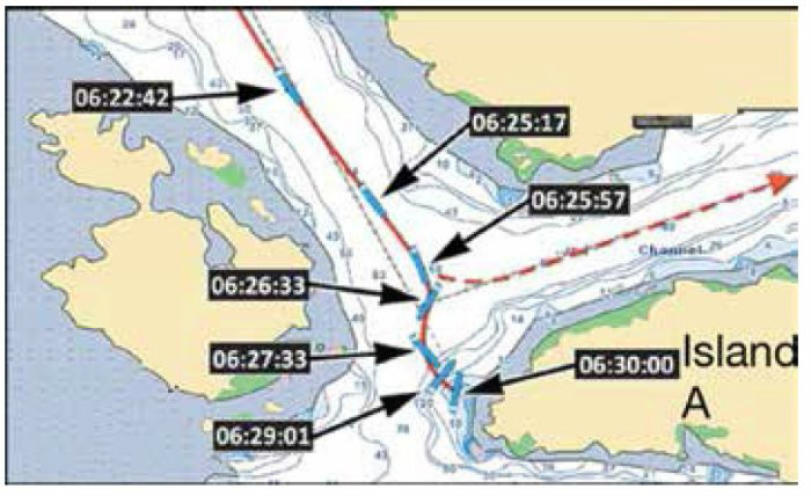

The OOW, who had the con for the first time in this area, requested that the Master take over before the large alteration to port at Island A (see below), approximately 0.7nm before the next course change waypoint. The Master took over the con and the OOW went to the chart table and began preparing the next chart. The helmsman was manually steering a course of about 140°G and the vessel was now proceeding at 16.7 knots. The Master was monitoring the vessel’s progress on the starboard radar; he had set up a parallel index to determine when to commence the port turn. A parallel index line was also set up on a course of 071°T to maintain a distance of 0.22nm off the northernmost point of Island A.

At the planned wheel-over position, the Master ordered the helmsman to apply 10° port rudder to initiate the turn. The helmsman acknowledged the order by repeating it, but instead put the helm 10° to starboard. Within seconds, the Master ordered the helmsman to apply 15°. The helmsman looked at the rudder angle indicator and repeated the order, but put the helm to 15° to starboard. Then, the helmsman asked for clarification about the direction of the order. The Master ordered the helm be applied faster without indicating the direction. The helmsman then stated that the helm was at starboard 15°. The Master ordered the helm hard to port. The helmsman acknowledged by repeating the order and applying maximum port helm (35°). The vessel’s speed was now about 15 knots.

Over the next three minutes, the Master continued to monitor the vessel on the radar as it swung back to port while querying information being provided by the OOW. At some point during this time the Master applied astern propulsion. Nonetheless, the vessel made bottom contact west of Island A on a heading of 012°G. The engines and the bow thrusters were used to manoeuvre the vessel back into the channel, and the vessel continued its voyage while the crew sounded the tanks and checked for damage. A crack approximately 0.6m long was found in No. 3 port water ballast tank that was allowing water ingress.

The official investigation found, among other things, that:

- At the time of the occurrence, three of six fatigue risk factors were present for the Master and for the helmsman: acute sleep disruptions, chronic sleep disruptions, and desynchronisation of the circadian rhythm. Both exhibited performance decrements consistent with fatigue, contributing to the bottom contact.

- The officer of the watch ceased participating in the monitoring of the vessel’s progress after the Master took over the con so was not in a position to readily detect the helm error or to assist the Master in responding to it.

Editor’s note: Many of us have experienced helm error and often it is corrected quickly and without serious consequences. In restricted waterways like this example, the margin for error is slim. One technique to help mitigate the consequences of helm error in restricted waterways is for the officer who has the con to closely monitor the helm order as executed via the helm angle indicator or by sighting the helmsman during the manoeuvre. In this case, since fatigue was involved, even these techniques may not have been sufficient to avoid the grounding, as being fatigued is the equivalent to being drunk. Avoiding fatigue is every mariner’s responsibility and not just a paper exercise.