201415 Collision in good weather and visibility

Edited from official Maritime Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) report 17/2013

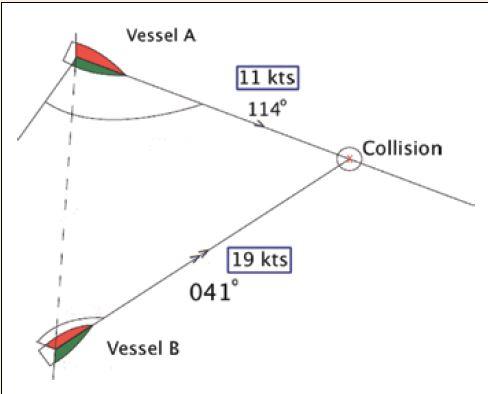

Vessel A was making way on an auto-pilot heading of about 104 degrees at a speed of 10.8 knots with an experienced OOW and an ordinary seaman as lookout on the bridge. It was night, but visibility was good. Vessel B was on an auto-pilot heading of about 043 degrees and a speed of 19.5 knots with a lone, but very experienced, watchkeeper on the bridge. Information obtained from vessel B’s voyage data recorder indicated that the watchkeeper occupied himself with tasks other than those exclusively of navigation and lookout.

At about 0515, vessel A’s lookout alerted the OOW to a vessel on his starboard side. The OOW determined that the vessel was overtaking his ship on a course of around 090 degrees and would pass 3 or 4 cables clear down his vessel’s starboard side. He attempted to plot vessel B’s radar target, but was unsuccessful: he did not take a visual bearing of the vessel. Some 17 minutes later, the two vessels were less than 3 nm from each other and on a collision course. At about this time, or soon after, the

lookout on Vessel A warned the OOW for a second time about the other ship on their starboard side. As the distance between the two ships further reduced, the lookout alerted the OOW for a third time to the presence of the other ship.

The OOW started to alter his vessel’s heading slowly to port; he predicted that this adjustment would increase the passing distance of the two ships. Shortly afterwards the lookout shouted for the OOW to ‘do something’. The OOW now realised that a

collision was imminent. He put the steering controls into manual mode and turned the helm hard to port. Meanwhile, vessel B’s watchkeeper first saw vessel A very close on his port bow but was unable to take avoiding action in the short time now available to him.

Some of the findings of the official report were:

* Vessel A’s OOW did not establish that vessel B was on a steady bearing, and that his was the give-way vessel. The inaction of vessel A’s OOW showed a total disregard for the safety of his vessel and his shipmates. Despite his experience and knowledge of the Colregs, he made an unfounded assumption that vessel B would pass clear of his vessel.

* Vessel A’s OOW did not assess the situation correctly initially, or reconsider his assessment when the situation did not develop as he expected. Even in the scenario that he had imagined, he was willing to accept a CPA that was much less than specified in the Master’s night orders.

* It is extremely difficult to determine a vessel’s aspect at night and, even if correct, aspect is no guarantee of a vessel’s acting heading or course.

* The complacent attitude of vessel A’s OOW, his misplaced belief in his ability to assess the risk of collision by eye, and his underestimation of the chance of encountering another vessel at close quarters combined to prevent him from taking the necessary actions to prevent the collision.

* Vessel B’s watchkeeper did not post a lookout or set the watch alarm, and instead relied on his ability to maintain an effective lookout on his own.

* Vessel B’s watchkeeper allowed himself to be distracted by tasks other than navigating and keeping a lookout, possibly by placing himself in a position where he could not see out of the bridge windows or look at his navigation aids.

* In choosing to take the watch alone and not setting the watch alarm, the watchkeeper on vessel B demonstrated extremely poor judgment, systematically overcoming each of the safeguards that should have been in place for keeping an effective navigational watch.

* The lack of regard of vessel B’s watchkeeper for his primary roles as lookout and officer in charge of a navigational watch can only be assessed as complacent.

Editor’s note: One would like to think that every collision is avoidable. All the more so in uncongested waters with good visibility/weather and ships manned by experienced watchkeepers. In the official report, complacency is cited as a major contributing factor on both vessels. While this is most certainly true, complacency, in and of itself, is not a root cause. If the experienced watchkeepers of both vessels were so complacent in this instance, so too must they have been at other times. Why wasn’t this behaviour picked up and corrected earlier? Often, such unacceptable practices are allowed to persist due to poor management and weak leadership; exactly the deficiencies ISM is meant to counteract. Ironically, ISM is not a silver bullet in this respect; ISM is not a substitute for good management and strong leadership.

Editor’s note: One would like to think that every collision is avoidable. All the more so in uncongested waters with good visibility/weather and ships manned by experienced watchkeepers. In the official report, complacency is cited as a major contributing factor on both vessels. While this is most certainly true, complacency, in and of itself, is not a root cause. If the experienced watchkeepers of both vessels were so complacent in this instance, so too must they have been at other times. Why wasn’t this behaviour picked up and corrected earlier? Often, such unacceptable practices are allowed to persist due to poor management and weak leadership; exactly the deficiencies ISM is meant to counteract. Ironically, ISM is not a silver bullet in this respect; ISM is not a substitute for good management and strong leadership.