202529 Wake up with a bump

MARS Report 393 | July 2025

As edited from TAIC (New Zealand) report MO-2024-201:03t

A small passenger vessel offered overnight tourism trips from a home port. It took various routes depending on the conditions at the time, but all were well known to the Master. Each day, a new group of passengers boarded for a 24-hour overnight cruise. The Master and crew worked this routine for seven days before being relieved by another crew in rotation.

In this instance, the Master and crew were in their sixth day of work in a seven day ‘swing rotation’. The Master’s workday started at around 0600 and finishes at about 2200. This ostensibly allowed for about eight hours of overnight rest. Yet, the quality of sleep is difficult to determine; sole-charge Masters bear full responsibility for their vessels and their sleep may be broken by any number of interruptions, including changes in weather and vessel movements.

On this day, the Master had awoken at 0545. By 1430, a new group of passengers had boarded and the vessel transited to an area where passengers could participate in water activities. By 1740, the anchor had been weighed and transit began to a new location. The vessel was being conned by the Master, alone in the wheelhouse as was the usual practice.

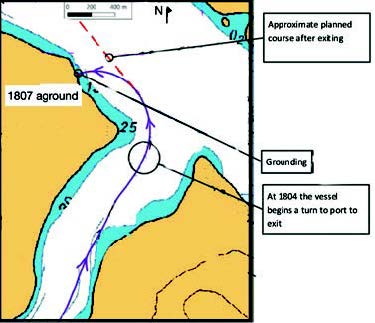

At approximately 1804 the Master began a turn to port. Three minutes later the vessel ran aground while at a speed of about 10 knots. Sitting in the conning chair, the Master woke from a micro-sleep when the vessel came to a sudden stop. The situation was quickly assessed and emergency response was begun; passengers were mustered using the public address system and the onshore manager was called to alert them to the accident.

The crew reported to their muster stations. Two crew were assigned to damage assessment and one to operate the bilge pumps. The remainder had roles mustering passengers and assessing them for injuries. The vessel damage included a small hole below the waterline, but the rate of water ingress was not a material threat to the safety of the vessel. The use of a small bilge pump was enough to clear incoming water.

By 1920, the tide had risen enough to lift the vessel off the rocks and enable the stricken vessel to get underway. The passengers were transferred to some fishing vessels and departed for the home port at about 2000. The stricken vessel began making way for the home port by 2230 and was alongside near midnight.

The investigation found, among other things, that the Master was very likely suffering from workload-induced fatigue that had not been recognised or mitigated by the operator’s safety management system (SMS). The fatigue may have been compounded by a potential drowsiness side effect from a prescribed medication the Master was taking, but it was not possible to make a positive determination on this hypothesis.

Lessons learned

- Micro-sleep exists, even while undertaking an active manoeuvre. If you can fall asleep at the wheel of a car, you can fall asleep at the con of a vessel.

- Sitting while navigating is one step towards further relaxation. Standing and moving (between navigation instruments?) means you are unlikely to experience a micro-sleep and may help your situational awareness.

- ‘Sleep hygiene’ is a critical element of safety in the transportation industry, yet one that is mostly self-managed. Take it seriously.

- Be aware of the potential side effects of certain prescription medications and how they can affect your performance.