202044 Collision involving a vessel adrift

Collision involving a vessel adrift As edited from official MAIB (UK) report 07-2020

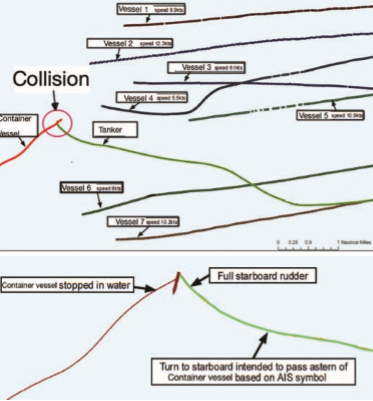

A container vessel was adrift in dense fog, standing-by off a busy port waiting for berth availability. Several other vessels were detected on radar but, due to the fog, could not be observed visually. The engine remained on immediate notice and the upper deck lighting was switched on. The traffic level was assessed as moderate with at least eight other vessels underway nearby.

Meanwhile, a tanker was approaching the same port. The Master of the tanker was at the con for the approach to the pilot boarding position.

A few course alterations were executed to avoid potential close quarters situations with several vessels. The tanker’s Master observed a new radar contact about 2.4 nm ahead. From automatic identification system (AIS) data, he established that the new contact was the container vessel and, from the orientation of the AIS symbol, he assumed that it was heading in a south-westerly direction.

The Master also observed that the container vessel’s AIS navigational status was ‘underway using engine’. The tanker’s OOW was monitoring the situation and noted that the container vessel’s predicted closest point of approach (CPA) was 0.3 nm on the tanker’s starboard side. In reality, however, the container vessel was stopped in the water on a heading of 197°. Due to the north-easterly current, its course and speed over the ground was 060° at 2.2 knots.

On the container vessel, the OOW was aware of numerous vessels approaching on the port side. Because of the poor visibility and his increasing concern about the possibility of collision he sent the deck cadet to the port bridge wing to keep lookout there. He did not, however, call the Master who was sleeping. Back on the tanker, the Master was talking with the OOW of another vessel in the vicinity on VHF radio.

The tanker had just made an alteration of course to starboard, intending to avoid the container vessel by passing its stern. This course change was also intended to increase the CPA with the vessel he was speaking to, which was approaching to port. With the tanker making 13 knots, and noticing that the CPA of the container vessel had not increased as expected, the tanker’s Master put the helm hard to starboard.

At the same time, the OOW of the container vessel noticed that the CPA of the tanker was reducing, so he used the VHF radio to attempt to establish communications with the tanker’s bridge team, but it was already too late. Just moments prior to collision, both the Master and the OOW of the tanker saw the superstructure deck lights of the container ship emerging from the foggy darkness ahead; the lights were spotted very close on the port bow. The tanker’s port bow struck the container vessel’s port quarter. None of the container vessel’s bridge team saw the tanker, including the deck cadet, who was on the port bridge wing.

Lessons learned

- Whether you are at anchor or drifting, don’t assume other vessels will stay clear of you. l Always keep your AIS navigational status up to date to reflect your vessel’s actual condition. l It would appear that many of the vessels in the vicinity of the collision, including the tanker, were proceeding at speeds that were arguably not really safe given near zero visibility and the density of the traffic.

- Paradoxically, even the container ship, which was drifting, could be considered as not proceeding at a safe speed because this gives very limited options for manoeuvring at a moment’s notice.

- While AIS data can certainly enhance situational awareness, radar target and ARPA data should always be used in preference to AIS to determine if risk of collision exists.

- As OOW, if you perceive danger or have concerns, always call the Master regardless of the hour.