200711 Unberthing in a squall

With the evening approaching, and given the absence of a night harbour pilotage service, we were anxious to depart from a west African port. Our handy-size, multi-purpose vessel was berthed head-in, starboard side to and had already singled up with pilot on board. We were awaiting the arrival of the only operational harbour tug, which appeared to be having some engine problems as she drifted midstream in the freshening breeze. The offshore (port) anchor had about two shackles in the water.

A bank of dark clouds was swiftly moving from inland. About 10 minutes later, while the pilot and the port control were still trying to establish contact with the tug on the radio and with liberal use of the ship's air horn, a violent line squall descended on us with blinding flashes of lightning and deafening peals of thunder. Rain fell in torrents and with that and the roaring wind, communications even within the bridge team proved difficult. All radio and talk-back contact was lost with the mooring stations, the last feeble message received from them indicated that the lines were bearing too much weight, which the master instructed to be cast off. Thereafter, we were all frozen in a state of suspended animation, utterly helpless and completely at the mercy of nature.

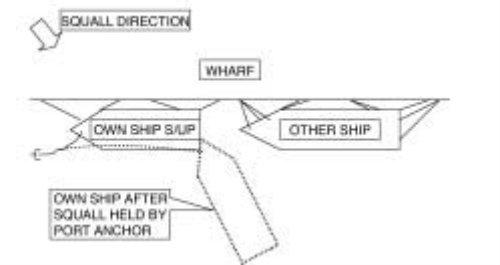

After the squall cleared, in about 10 minutes, we were horrified to see that our ship was lying at right angles to the wharf with our stem only a few metres from the vessel at the next berth astern, only the taut anchor chain having averted a contact. The singled-up lines had either parted or had been cast off from the shore, without the knowledge of the crew. The shore was a scene of devastation. Water was pouring out of the warehouse doors, the roofs having sprung leaks. The wharf was submerged knee-deep by a raging stream rushing down from the slightly elevated ground beyond. Empty containers were drifting in the flood, while water had entered those with cargo. The tug that was last seen approaching about three cables away had been blown offshore by about half a mile and appeared to be still out of order. Taking quick advantage of our relatively 'advantageous' orientation, the port anchor was quickly heaved up and with a single astern engine movement, we were able to safely clear the wharf and head out to sea. The next nasty surprise came when the pilot, now soaked to the skin, prepared to disembark. The pilot launch, which was last reported to be waiting at the charted position, a mile or so seaward from the berth, had also broken down, apparently having taken in a lot of water via a dislodged engine room hatch. Fortunately, in the gathering dusk, we hailed a passing fishing boat and managed to disembark the pilot safely.

Lessons learnt

Line squalls, especially in the tropics, can develop without warning and can turn very violent.

Berthed vessels must take all possible precautions to ensure they remain safely secured.

Vessels at anchor must consider heaving anchor and heading to open water or letting go the second anchor, if practicable.

The main engine must, in any case, be kept ready for manoeuvring.

Unberthing or berthing operations that are in progress must be aborted as soon as a squall is seen, although, in the above incident, it would certainly have involved a 12-hour delay and departure the following morning.

Portable VHF radio transceivers (walkie-talkies), talk-back speakers and microphones must be always protected within weather-proof plastic covering.

A simple sound signalling code on the ship's whistle for mooring operations could be part of the ship's contingency plans for circumstances when normal communication systems fail.