Free Article : Jamming and Spoofing

Recognising and dealing with threats to marine navigation systems

Captain Johan Gahnström AFNI

In September 2020, the USA’s Maritime Administration (MARAD) issued a notice warning of multiple instances of GPS interference in various parts of the world, including the eastern and central Mediterranean Sea, the Persian Gulf, and multiple Chinese ports. This once again shines a spotlight on the vulnerabilities and threats to our marine navigation systems.

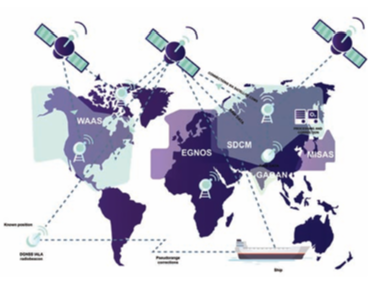

High standards of marine navigation are fundamental to the safety of vessels, crews, cargoes, and the protection of the environment. We are more and more reliant on types of Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) like GPS for safe navigation. Today several GNSS systems exist beyond GPS such as GLONAS, BEIDOU and GALILEO that all now have global coverage at high precision.

Growing threats to these systems have been identified that can affect how we use them for navigation and how we can mitigate against disruption to services provided by GNSS.

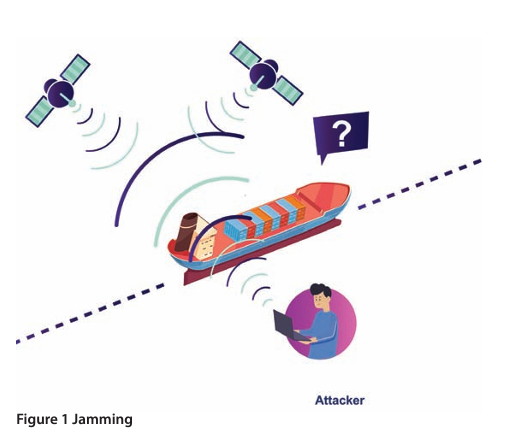

What is jamming?

GNSS signals have low power, which means that a weak interference source can cause the receiver to fail or to produce hazardously misleading information.

Complete loss of GNSS is easy to detect, but subtle movements due to the effect of jamming are not – and can appear similar to spoofing, which can be very hard to detect. Jamming does not require expensive tools or expert knowledge.

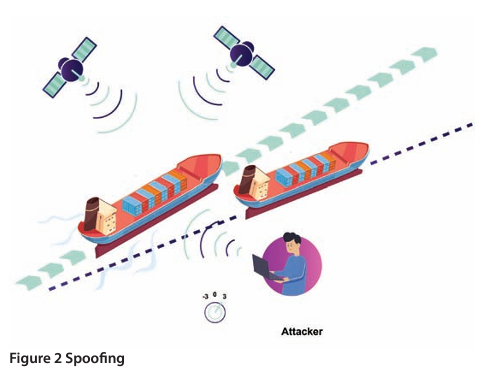

What is spoofing?

GNSS spoofing is the provision of GNSS-like signals, transmitted locally and coded to fool the receiver to think it is somewhere it is not. These spoofed signals may be modified in such a way as to cause the receiver to estimate its position to be somewhere other than where it actually is, or to be located where it is but at a different time, as determined by the attacker. Spoofing GNSS signals with the aim of not being detected is a military grade technology, and currently unlikely to be seen in peacetime.

'Meaconing’ is a type of spoofing where GNSS signals are re-transmitted. This requires simpler equipment than that required for a spoofing attack.

A spoofing attack is considerably more complex than a jamming attack, especially if the attack is supposed to remain undetected. To simplify, jamming causes the receiver to die, spoofing causes the receiver to lie.

Countermeasures

- Fortunately, there are multiple risk mitigation strategies to help overcome interference to maritime navigation systems:

- Filtering in the receiver. This is especially effective for out-of-band signals, but unfortunately, if a signal falls directly in-band it may still overpower the receiver.

- Consider using Loran/E-Loran receivers as a backup/part of the resilient system and a way to detect jamming and spoofing. (Note: these do not have worldwide coverage.)

- Development of advanced mitigation techniques using wideband GNSS signals like Galileo E5 could be seen in the future.

- With respect to jamming, various GNSS deliver different services at different frequencies. For the Open Service and for maritime receivers type-approved against IEC 61108-3, the frequencies are at E1 and E5 position. Using different frequencies will to some extent mitigate against an attack, but it does not necessarily mean the system will work through it.

- Some types of GNSS will soon provide Navigation Message Authentication (NMA), which involves a signal consisting of some parts that cannot be generated by a spoofer. An example is Galileo’s Open Service Navigation Message Authentication (OSNMA).

- If the equipment onboard meets the MSC.1/Circ.1575 specification and there are multiple types of GNSS as well as other inputs, the system should raise an alarm in case of a detected error to inform the navigator that the position has been lost. Modern equipment already exists that meets the MSC.1/Circ.1575 guidelines.

How to detect jamming and spoofing

- Actions to detect GPS spoofing and jamming should include the use of radar and ECDIS interlay (overlay or underlay). These are by far the best methods to identify jamming and spoofing when land is visible on the radar.

- Position verification at appropriate intervals.

- Observing significant difference between DR position (position arrived with gyro course steered and distance by speed log) and GNSS fix.

- Observing and verifying by using an echo sounder to compare the depths, when sailing in suitable depth areas.

Actions if jamming and spoofing is detected

Immediate actions:

- Manually select a secondary position sensor. Select other GNSS input if provided and if it is working.

- If the secondary sensor is unable to provide a vessel’s position and no other means are available to input position fixing, the navigator must select the DR or EP mode.

- Start to manually plot ship’s position if near enough to shore and seek greater sea room if possible.

- The AIS is likely to be affected by a jamming or spoofing attack and should be used with extreme care. This is because other ships’ GNSS input positions are highly likely to be affected as well as own ship.

- Use the parallel indexing method during coastal navigation to keep safe distances and determine turning waypoints.

- If unable to ascertain vessel position relative to navigational hazards, then stop the vessel.

Training

Training is the best way to be prepared for a jamming and spoofing attack. As an example, a drill could include switching off the GNSS sensor/s in a safe area, with the ECDIS needing to be operated with manually-inserted positions in dead reckoning (DR) or estimated position (EP) mode. The OOW should be able to identify other equipment affected by GNSS sensor failure (eg. AIS, Digital selective calling-DSC, gyro and radar). The aim of the training is to develop competency in detection of GNSS jamming or spoofing and safe navigation practices that are independent of GNSS. So smooth sailing and no jamming and spoofing.

Captain Gahnström is today the shipping operations director at LOC London. He is a master mariner with a background as Master, maritime pilot, VTS manager and Harbour Master. Captain Gahnström worked for five years with Intertanko as their navigation, ports & terminal expert.