202041 Car carrier kerfuffle

As edited from official MAIB (UK) report 6-2016

A pure car-truck carrier (PCTC) was in port loading vehicles. The chief officer (CO) was in the ship’s control centre using the ship’s ballast system to ensure that the vessel remained stable throughout loading and maintained a favourable trim. Previous calculations indicated that the ship would have a metacentric height (GM) on departure of 1.46 metres. This was acceptable, but smaller than was usual.

As the loading progressed, arrangements were made to load some additional high and heavy cargo that was on the reserve cargo list. Neither the ship’s duty deck officer nor the CO were advised of the additional cargo before loading. Later that day, cargo operations were completed and draughts forward and aft were read and reported to the CO, who then made a standard adjustment to the reported aft draught that allowed for the stern ramp still being on the quay.

This gave departure draughts of 9.0 metres forward and 8.4 metres aft. However, these were mistakenly reversed when recorded on the bridge noticeboard and on the pilot card. A pilot embarked and the final cargo tally and stowage plan was delivered. The stern ramp was lifted in preparation for departure and the ship listed to starboard.

The pilot commented on the list, which was estimated at 7°, well in excess of the 1° or 2° normally experienced when the ramp was lifted.

The CO went to the ship’s control centre and transferred ballast water from the starboard heeling tank to the port heeling tank, bringing the ship upright. He then proceeded on deck to supervise the unmooring operation. The Master, pilot, third officer and helmsman were on the bridge.

About 20 minutes after departure, the CO and the deck cadet went to the ship’s control centre to commence departure stability calculations. Due to a large number of changes between the planned load and the actual load, the CO decided to re-enter all of the cargo figures rather than amend the departure stability condition that he had used for his calculation earlier in the day.

As the vessel proceeded outbound from the port, the Master telephoned the CO and told him that he thought the ship ‘did not feel right’. The CO replied, ‘I’m working on it’. Within minutes, the pilot gave the first helm order, which was to starboard, with the ship making good a speed of 10 knots. The first turn was completed without incident, the ship heeling to port and returning upright as expected. Shortly afterwards, the vessel entered a channel and the pilot requested that the ship’s speed be increased. Meanwhile, the CO became concerned that the newly calculated GM was less than his earlier departure stability calculation had predicted. Since the automatic sounding gauges were out of order, he sent the cadet to take soundings of the three aft peak tanks in preparation for loading additional ballast water.

The CO then began setting up the ballast system using the mimic panel in the ship’s control centre. He anticipated that he would require an additional 300 tonnes of ballast in the aft peak tanks. The vessel was now making good a speed of 12 kt. The pilot gave a sequence of orders to the helmsman to execute a port turn: ‘Port 10’, then about a minute later, ‘Port 5’, followed by ‘Midships’. He observed that the vessel was behaving uncharacteristically during the turn and noted, ‘She’s very tender, Captain’. The ship then progressively heeled to starboard and the rate of turn increased rapidly.

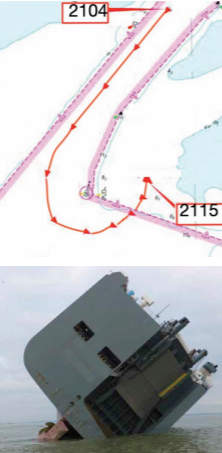

The pilot ordered ‘hard a starboard’ and ‘stop engines’. He inquired about the vessel’s GM but it was already too late. The vessel blacked out and the starboard list continued to increase as the ship swung to port and grounded, (top left) its rudder and propeller now clear of the water (bottom left). Rescue and salvage operations were subsequently undertaken.

Some of the findings of the official report were;

- The vessel had inadequate residual stability to survive the port turn at 12 knots and did not comply with IMO stability requirements. l The vessel’s actual cargo weight and stowage were significantly different from the final cargo tally supplied to the ship. l Several unsafe practices or pre-existing conditions contributed to the vessel’s inadequate sailing stability, including;

- Cargo unit vertical centres of gravity (VCGs) were not considered when calculating the stability condition; - Ballast tank quantities were estimated and differed significantly from actual tank levels; - Most of the cargo weights supplied by the shipper were estimated rather than actual values. In reality, there were significant differences between the two for several cargo units;

- The vessel’s stability was not determined until after departure, which was routine practice on this vessel; - The company’s port captain saw little value in involving the chief officer or the Master in any decision-making processes; - The company’s operations manual provided no guidance on the role of the port captain, nor how the chief officer and port captain should cooperate to best effect;

- The process of applying estimated figures to previously estimated figures, and to adjust those figures to compensate for draught readings compounded to allow a ballast condition for departure that bore no resemblance to reality;

- The chief officer’s familiarisation on joining the vessel had not included instruction on the use of the loading computer;

- The need to accurately calculate a ship’s stability condition for departure and voyage did not feature in the company’s two-day training course for newly assigned senior officers to its PCC/PCTC fleet.

- Lessons learned: The investigation uncovered evidence that suggests sailing without a finalised and accurately calculated GM is a practice that extends to the car carrier sector in general. l Without proper training it is likely that unsafe practices will become the norm. l When unsafe practices become the norm, it is only a matter of time before an accident occurs.

- Editor’s note: Ballasting operations and stability calculations (before departure) are particularly important for car carriers and roro vessels. A number of major casualties have resulted with these vessels, which must, in the final analysis, be related to less than adequate training and procedures in these areas, not to mention commercial pressures that normalise unsafe practices. A partial list of these casualties include the accident under review here (2015), the Cougar Ace (2006), the Finnbirch (2006), the Dany F II livestock carrier (43 crew lost, 2009), the Riverdance (2008), the Modern Express (2016), and more recently, the Golden Ray (2019). When these vessels make turns of 45° or more, the extreme potential negative consequences, in lives, material, and damage to the environment, are astonishing. It is baffling why the companies involved are not more stringent in their training, practices and procedures, to say nothing of their audit processes.