Introduction

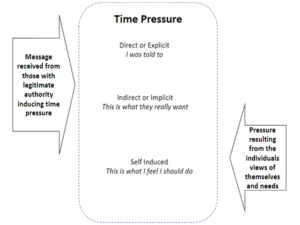

This part of the guide offers plain language explanations of the measures ports and terminals may adopt to address the risk presented by excessive time pressure on seafarers and port workers alike. This part of the Ports/Terminals guide focuses specifically on time pressure.

The guidelines are non-prescriptive and seek to identify aspects of port operations that have the potential to introduce time pressure on ships’ crew and port workers alike. The guidelines describe measures that may be taken to mitigate the associated risk and may inform the due diligence associated with port and/or terminal nomination within the scope of a ‘safe port warranty’.

Ports and Terminals Guide

This section of the guide aims to explain the background and where direct pressure may arise from.

Background

In common with the ships that use them, ports and terminals are increasingly capital-intensive assets, their earnings a function of the number of ships that visit and the volume of cargo handled. Put simply, the less time a ship is on the berth the greater the profitability of the port, and the higher the port’s ranking on global efficiency league tables:

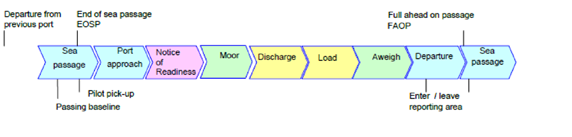

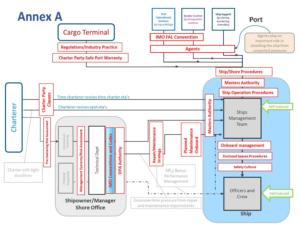

Furthermore, any delay in completing a ship’s loading and / or discharge cycle (shown in figure below), commonly known as demurrage, represents an additional, and often disputed, cost for the stakeholders involved; the resolution of demurrage claims is an everyday battleground for the ship owner and charterer alike although this depends on the nature of the trade, tramp operations – particularly dry bulk - more so than liner operations. The overriding commercial imperative, therefore, is to reduce port time – even in those circumstances where this has minimal, if any, impact on the overall length of the voyage cycle; ships may spend extended periods at anchor but see below.

For the dry bulk trades, port and/or terminal time pressure is recognized by IMO as a significant risk factor, the Bulk Load Unload (BLU) Manual requires, among other things, ship and terminal management agree a load/unload plan, with timings, prior to commencing cargo operations.

However, with the ever-present demand to increase port/terminal cargo throughput, particularly but not exclusively the handling of containers, time pressure has been cited as a causal factor for incidents involving a wider range of ship types, for example Ro-Ro loss of stability and loss of containers overboard consequential to a failure to stow/secure in compliance with IMO standards. In other words, there is inadequate provision to enable the ship and port/terminal to complete the procedures required to ensure cargo operations can be safely undertaken and/or the ship is seaworthy prior to port departure.

In addition, due to limitations on storage, tugs, pilots, channel tidal and navigation limits etc., any delay to a ship’s departure can rapidly escalate with potentially critical disruption to the ‘just in time’ supply chains that characterize logistics. If the modelling identifies a risk of delay, then that will be discounted against the capital and delays (demurrage) to ships built in. In such circumstances, the design demurrage becomes a means to reduce capital expenditure (CAPEX) for ports. In the context of operations, therefore, demurrage may become a target to reduce which, within limits, is deemed acceptable. Beyond these limits, ships may be pressured to berth in marginal weather or directed to reduce their time on berth. In short, the 'design for operation' philosophy that informs port design is flawed as it is 'operating to design' with margins reducing over time.

Much of the time pressure related to port operations may, consequently, be viewed as a means to the end of minimizing demurrage and/or CAPEX. In the immediacy, said pressure/workload principally impacts ships’ crews, shaping their behaviour and decision-making, crowding-out essential safety related tasks established in regulation and/or best-practice, for example the completion of a ship-shore checklist and other pre-arrival information exchange between ship and port/terminal staff. So doing may also impact the safety of shore-based personnel who have – or arguably have not – cause to board the ship in port.

Finally, an often-overlooked aspect of port operations is a commonly held presumption on the part of port stakeholders that ships’ staff have access to all information necessary to plan the port call. However, the information in pilot books and port entry guides or other sources of public domain information may often be out of date or limited. Nonetheless, a ship is expected to operate at peak efficiency throughout the port call with little regard from the port authorities as to how this can be achieved without the most basic and essential information being available to facilitate a proper port call plan. Moreover, without access to the relevant information, there is the potential for a lack of understanding of local culture and practice, on both sides.

Direct time pressure in Ports/Terminals

In port, pressure is exerted on a ship’s crew in port by a diverse range of stakeholders each driven by their own agenda. This sections looks at direct time pressure:

Direct time pressure in ports

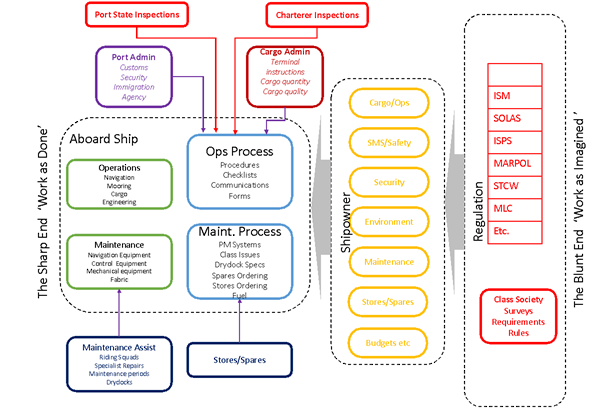

In port, pressure is exerted on a ship’s crew in port by a diverse range of stakeholders each driven by their own agenda. A small army may descend on the ship demanding the immediate and undivided attention of senior staff (Figure 4). This includes: -

1. Government bodies - police, immigration, customs, and health.

2. Port State Control Inspectors

3. Cargo inspectors/agents - to inspect tanks / holds in readiness to receive cargo or affirm the cargo has not been damaged in passage.

4. Berth operators - subject to their own time / commercial pressures to turn around ships in fulfilment of time critical 'efficiency standards' established by international trade bodies, and increase their ranking on league tables established by said trade bodies.

5. Owners - Who may have requirements for repairs, superintendent visits etc.

6. Classification Society Surveyors

7. Loading stores, spares, bunkering, and

8. Agents - as discussed below.

In days past, additional staff such as the Catering Officer/Purser and/or Radio Officer were available on a ship to front port personnel. With developments in technology and regulation, the aforementioned have long since been dispensed with, the burden of handling port/terminal bureaucracy largely falling on the master alone, particularly if Agent support is reduced.

In addition to regulatory bodies, depending on the ship type, stevedores and other port personnel will similarly seek to access the ship. This may represent a security, and health and safety management challenge for the master, who is responsible for their wellbeing at all times, particularly if port personnel seek to access enclosed spaces without issue of a Permit to Work (PTW) by the ship, or fail to comply with the conditions of the PTW, and/or are exposed to fumigated or other hazardous cargo. Typically oversight of stevedores etc. is discharged by the chief officer, in addition to his or her key functions of stability management and cargo storage/securing, notwithstanding he or she may have been on duty many hours previous to berthing and, therefore, requires rest.

Understanding ship/port operation

The first step in a successful port visit is to understand how the ship works. A number of important factors need to be understood in the way that a ship operates and is regulated.

The ship is governed by the laws of its Flag.

A ship is governed by the laws of its flag state. However, while in port, local port regulations will also apply to the conduct of the ship and its crew.

The Master is in control of the ship and access to the ship.

Even in port, the master exercises overall responsibility for the safety and security of the ship, including the access of all shore personnel and all cargo-handling activities as performed by stevedores or other port / terminal personnel. The master – in practice, the chief officer - should be able to control access via a security watch at the gangway and establish a briefing and / or proactive monitoring regime for shore-based staff who require access to the ship for cargo operations.

Therefore, it is the prerogative of the ship’s master and staff to determine when shore personnel are permitted to board, which may include delaying the landing of the gangway until such time as the ship’s crew are ready to take on their responsibilities in supervising access.

Permit to Work - Locked Access to Holds / Tanks

While on the ship, as introduced above, shore staff are subject to the jurisdiction of the flag state/master together with the regulations and standards of the IMO, notably the International Ship Management (ISM) Code and the Safety Management System of the ship established in compliance with the Code. Among other things, shore staff must not access holds, tanks or other ‘high risk’ enclosures other than in accordance with the ship's ISM Safety Management System (SMS), which may include a Permit to Work (PTW) issued on behalf of the master required to do so. It is unlikely that shore staff will understand and adopt the ships PTW systems and the requirements of that document/system need to be translated into understandable actions and restrictions for shore staff. This may be by supervision, restriction of access, signage or locking access to these spaces until it is considered safe for access.

Fatigue Management

Measures are established through regulation that, in principle, require ships’ masters and other critical staff prioritize rest, to mitigate and manage their fatigue. That a ship has recently arrived in port, and the expediency of commencing cargo operations as soon as possible, does not obviate statutory rest.

Safe Manning

Safe manning regulations and associated guidance require a ship to be sufficiently, effectively, and efficiently manned to provide safety and security of the ship, safe navigation and operations at sea and safe operations in port. And, by extension, to ensure there is sufficient resource to facilitate ships’ staff maintaining statutory rest without compromising the safety of port operations. Safe manning does not. however, mean unlimited resources are available for simultaneous labour-intensive operations.

For example when the ship is moored ‘all fast’ the crew will require time to ensure working areas are tidied and made safe before allowing visitors to board.

Completion of Ship/Shore Safety Checklist

As required by IMO regulation for certain ship types, and best practice otherwise, no port-related operations should be undertaken without a detailed exchange of information between ship and port/terminal operator prior to arrival and commencing port operations. This includes completion of a ship/shore safety checklist duly signed by representatives of port and ship.

Prior to the commencement of cargo handling, and the deployment of stevedores, a ship/shore safety meeting should be convened, including a final review and confirmation of the arrangements for, among other things, hold or other enclosed space access, and to ensure each side is fully briefed and aware of their respective responsibilities towards one another.

Tanks/Hold Properly Ventilated Before Berthing

In general, there is an expectation that the ship is cargo worthy prior to loading, i.e., all hatches or tanks are fit to receive the nominated cargo. This would normally require the crew perform cleaning in the time available between discharge and loading ports without compromising the timing of issuing the Notice of Readiness (NOR) - often a critical condition of the contract between ship owner and charterer in terms of determining subsequent costs incurred. In bulk cargo discharge operations, the removal and environmentally compliant disposal of cargo residues is part of the ‘ventilation’ process, and when holds are full access trunks may not have been ventilated.

IMO Facilitation Convention

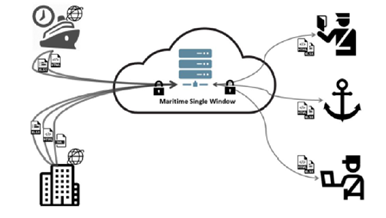

Among others, the purpose of the Facilitation Convention (FAL) is to simplify formalities, documentary requirements and procedures on ships’ arrival, stay and departure from port.

The FAL Convention mandates the use of modern information and communication technology for ship-shore information exchange, ideally using electronic data interchange (EDI) through a Maritime Single Window (MSW) (Figure 5), which serves to ease the burden on ships’ asters in particular. Furthermore, the use of a MSW removes the need for government / port personnel to physically attend the ship other than for direct operational reasons, all information exchange between ship and port finalised during the sea passage (Figure 3) by the agent or master as the case may be.

Agency

The first and perhaps key point of reference for information to masters of ships is the port agent. The agent should be in possession of the latest information regarding all aspects of the ship’s call, and not simply act as a go-between-communications-conduit as is often the case. The agent, therefore, fulfils an essential role, ensuring the ship is registered in the port system in good time, communicating relevant information to the Port authorities, Terminal and relevant government officials.

The agent, too, is under pressure. If the agent additionally serves the interests of the charterer / shipper, the agent may not be in a position to prioritize the requirements of the owners and crew. By contrast, where owners appoint their own protective agents or husbandry agents, they will exercise better control of their requirements noting that owner’s agent may be granted delegated authority to sign statutory shipping documents such as the bill of lading on behalf of the owner without the need for the involvement of the master/chief officer.

There have also been cases where a port agent handling crew changes is pressured by the owners’ manning agency, possibly operating under a fixed-budget contract, to send crew onboard direct from the Airport without accommodation and proper rest to avoid additional Hotel charges contrary to IMO recommendations on fatigue management.

Charterers' Safe Port Warranty

Depending upon the nature of the contract (charter party) between the ship owner and cargo interests, the latter is subject to warranting the safety of the port(s) designated for loading/unloading.

There are no formal regulations or standards applicable to the ‘safe port warranty’. On such occasions the issue has been raised in court post port operations, the meaning is determined on the merits of the individual case. Nonetheless, while largely considered to relate to the physical geography – or hydrology – of a port, there is nothing per se that excludes ‘soft’ issues from the warranty. Best practice advises charterers undertake due diligence on the port operator/terminal to verify compliance with all safety regulations in force, for example the BLU Code, and affirm the management of the ship-shore interface by the port is in all respects fit for purpose in compliance with the FAL Convention etc.

Specific issues - Port/terminal time pressure

ETAs and ETDs

The first obstacle is Arrival and Departure notification times. There is a misunderstanding in many quarters as to what the “E” stands for in ETA and ETD. The correct meaning is ESTIMATED and not “Exact” as many agents and other parties seem to believe. An estimation is an approximation, not an absolute value or quantity. A ship’s ETA or ETD is the approximate time that something is expected to happen, not the time that it will happen. Definitive timing arrangements should not be made based on an estimate alone unless there is an associated time envelope around the estimated time available, e.g., an allowance of an hour or more unexpected delay can be accommodated without penalty.

In practice many – but not all - ports and terminals use ETAs or ETDs to make both provisional and firm bookings for services. To reduce costs, and secure enhanced commercial efficiency, some ports offer little if any resilience in the provision of pilotage, the ship subject to a ‘use-it-or-lose-it’ policy if it fails to present at the agreed time, whilst others engage arguably non-productive resource to offer “windows” of several hours to accommodate last minute ETA / ETD variation due to unforeseen circumstances. Lack of this specific information can create unnecessary stress and pressures on board.

As with Pilots, similar situations apply to the availability and operational time envelopes for tugs and linesmen. Particularly in busy ports, tugs and linesmen may be in great demand and so are programmed for periods sufficient in normal circumstances to perform the required berthing or unberthing operations. If there is flexibility on changes to booking times or restrictions and late notice penalties, then this information needs to be available to the ship’s Master in advance of the port call.

Finally, in planning the port call, the terminal facilities, regulations and policies concerning early arrival or delayed departure to undertake on board operations, facilitate statutory rest periods etc. should be unambiguously available to the Master before arrival.

To summarise, in the circumstance where ships’ Masters and personnel are of the belief that all scheduled times are absolute, with financial penalties imposed on the ship, because they’re not told otherwise, this can lead to over-enthusiastic operational practices on board with associated corner-cutting, dispensing with or circumnavigating safe working practices and protocols leading inevitably to accidents or undesirable incidents. Much of this can be avoided by simply ensuring that the Master is properly and comprehensively advised of all operational restrictions and where appropriate liberal facilities applicable and available to the ship during its call. In addition, ports that invest to offer greater service flexibility and / or effectively communicate with ships should not be penalized or otherwise viewed to be less efficient than those that cut time and resource to the bone, quite the opposite in the context of determining whether or not the port can meaningfully be assessed as ‘safe’ through a process of due diligence.

Master’s and Senior Officers’ Workload in Port

As introduced previously, port arrival may involve long passages under the guidance of a pilot. In compliance with local port regulation, and most likely the SMS approved by the Flag State / Classification Society, the Master and/or other senior staff are required to be present in the wheelhouse throughout the pilotage, staff who have likely been on duty for a substantial period prior to the pilot’s embarkation, i.e., to navigate the congested waters that typify port approach.

Port compliance with the FAL Convention, in particular the obligation to accept only electronic documentation for regulatory clearance, is patchy at best. The expectation remains in many if not the majority of ports that the Master, in the absence of support staff, must personally deal with port authorities, who continue to come onboard regardless.

Throughout cargo handling operations, the chief officer is expected to be on call. Depending on the nature of the cargo, and whether the operations involve loading or unloading, or both, the aforementioned must, among multiple other tasks, dynamically evaluate stability and verify cargo security without breaching the port’s deadline for departure. The perception at least: failure to do so will invoke severe censure / personal financial loss for the chief officer; misguided professional pride a factor as well.

On completion of cargo operations, by convention and practice the Master is required to personally endorse cargo-related documentation, e.g., bills of lading, notwithstanding international shipping rules do not require this; the task can be delegated to an agent.

Finally, international maritime law empowers the Master to delay port departure if he or she – or other key member of ship's staff - feels unduly tired and unfit for duty, or the master is not assured that the ship is regulatory compliant/seaworthy. However, should this power be invoked, in addition to the perceived or actual personal censure of the master, demurrage costs on the ship owner will inevitably result. There may also be a wider impact if the actions of a master to delay departure prevent the arrival of the next vessel scheduled to discharge at the berth.

Weak Compliance

As reviewed above, a comprehensive regulatory framework is established by IMO, and others, to address the risk associated with port/cargo operations. This includes, among others, the Code of Practice for the Safe Loading and Unloading of Bulk Carriers (the 'BLU Code'), the Manual on loading and unloading of solid bulk cargoes for terminal representatives (the 'BLU Manual') and The Code of Practice for Safety and Health in Ports issued by the International Labour Organization (ILO).

However, like the failure to comply with the FAL Convention, the safety culture and enforcement regimes for ports are reportedly weak, particularly in developing countries.

Nor are ports alone guilty in failing to comply with regulations related to the port-ship interface. As recently reported by the Netherlands in a submission to IMO, a concentrated inspection campaign by the Port of Rotterdam established that 67% of the ships inspected violated SOLAS regulations relating to the loading and securing of containers prior to port departure. In the opinion of the report's authors, with low financial margins, and the need to 'work as efficiently as possible', this puts time pressure on ships' crews and others (e.g., stevedores) increasing the likelihood of errors and deficiencies.

Insufficient Staff Available to Control Access

As introduced previously, IMO safe manning standards require, among other things, sufficient personnel on the ship to undertake port operations – without specifying what functions must be discharged and / or the workload involved.

Maintaining control of ships’ access requires there be sufficient staff on – or at the behest of - the ship to carry out an effective gangway watch. Access by one person may mean access for all and stevedores, for example, may gain access and attempt to access holds without the master's consent in compliance with the ISM Code. With multiple other functions to be performed, in practice the ship may not have the personnel to control gangway access, which may also be seen as a requirement of the International Ship and Port Security (ISPS) Code. However, there is nothing to say those controlling access are drawn from the Safe Manning Certificate cohort. Moreover, contrary to the widely held belief of many port authorities, perhaps, responsibility to protect a ship from port-sourced security risks, such as unauthorised access, rests with the port not the ship.

Lack of Understanding of Shore Staff of ships and Shipboard Responsibilities

On a similar theme, shore staff may have little understanding of ships. This is notwithstanding regulation and standards in force that require, among other things, shore staff interfacing with ships – including casual staff engaged as sub-contractors – receive subject matter training. Anecdotal evidence is few port / terminal operators have formalized training in ship awareness albeit there are notable exceptions, e.g., Chile.

Agents

Most ships now have access to broad-band communications through satellite. Port agents come at cost. Owners may see engagement of the latter serves no purpose if the functions of port bureaucracy can be performed directly by the ships’ staff, which in turn potentially increases the pressure on the ship particularly if the port operations are not routine for any reason.

Power/Power distance

Ships’ staff can be at the wrong end of hectoring by officials who demand time and access as well as threatening to delay the ship if suitable ‘accommodation’ is not forthcoming. This is a complex area of behavioural science though may be resolved to a clash of culture between port and ships’ personnel, or a simple misunderstanding of each other’s culture. The outcome may lead to misunderstandings regarding discharge of responsibilities for safety and potentially unrealistic expectations of timescales to complete a task.

Design

The design of access to ships' holds or other facilities used for the storage / transport of goods, notably bulk carriers, may create a risk of trapped hazardous atmosphere. This issue is addressed in some depth by the previously introduced ILO Code of Practice, the ladder or other means of hold access and area of particular concern – notably the so-called 'Australian ladders'.

Ambiguity of Safe Port Warranty

The degree, or depth, to which the safe port warranty is given effect is purely a contractual matter between ship owner and charterer. Such is the nature of the power balance between parties; not necessarily in the favour of the charterer as currently being experienced in the container trades, the owner may fear the pressure (risk) of losing the contract through asking questions in relation to the efficacy of the port(s) nominated by the charterer outweighs the potential risks involved. And for the charterer, due diligence of a port is a potentially resource intensive activity for little reward if insurers remain content to cover the risk; that the port is not safe, including time management.

Good practices

For the reasons described above, there is marginal gain to be achieved through amendment of international regulation and standards; the aforementioned are already comprehensive in scope and detail. However, some good practices may be considered.

Establishing 'Protected Periods' in Port Operations

As shown on Figure 3, there is a finite period between a ship berthing and commencing cargo operations, and subsequently completion of cargo operations and 'aweigh'. As explained previously, for different reasons, both generate time pressure on ships’ staff.

The establishment of ‘protected periods' is an option to depressurise the situation. That is, ensure sufficient time is established in contract, be that between the ship and charterer or charterer and port / terminal, to prepare the ship for cargo operations, including the associated bureaucracy, and critically to secure the ship for the forthcoming voyage before leaving the berth on completion of cargo operations, for example, complete ballasting and stability calculations, and secure the cargo in compliance with IMO standards etc. The aforementioned periods should be excluded from the port time/demurrage.

In some US ports handling containers, a formal joint ‘walk round’ of the deck is required prior to the cargo area being used by shore staff. This would appear to be a good model.

Improve understanding by shore staff of ships and shipboard responsibilities.

Shore staff should be briefed, before boarding, on the ship and any hazards. They should also understand that they should not interfere with ships equipment and should follow the instructions of officers and crew about entry to enclosed spaces

Tighten access to ship using agents to control ‘appointments’.

Access to ships has been tightened during the COVID epidemic. Ports are responsible for access to the berths. Gangway watches should prevent visitors boarding the ship unless they are on a list of approved visitors. The agent should control this list.

Where to download the guides?

Diagrams

Annexes and further reading