Introduction

In common with the ships that use them, ports and terminals are increasingly capital-intensive assets, their earnings a function of the number of ships that visit, and the volume of cargo handled. Put simply, the less time a ship is on the berth, the greater the profitability of the port, and the higher the port’s ranking on global efficiency league tables.

Addressing time pressure in ports and terminals

This part of the guide offers plain language explanations of the measures ports and terminals may adopt to address the risk presented by excessive time pressure on seafarers and port workers alike. The guidelines descripe measures that may be taken to mitigate the associated risk and may inform the due diligence associated with port and/or terminal nomiation within the scope of a 'safe port warranty'.

There are a few operational challenges and safety risks in port and terminal operations, use the drop down boxes below to find out more.

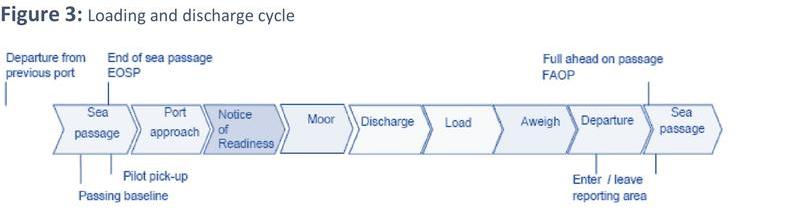

Any delay in completing a ship’s loading and/or discharge cycle (see figure 3), commonly known as demurrage, represents an additional, and often disputed, cost for the stakeholders involved. The overriding commercial imperative is to reduce port time, even in those circumstances where this has minimal, if any, impact on the overall length of the voyage cycle. Instead, ships may be rushed through operations in the port itself, only to then spend extended periods at anchor.

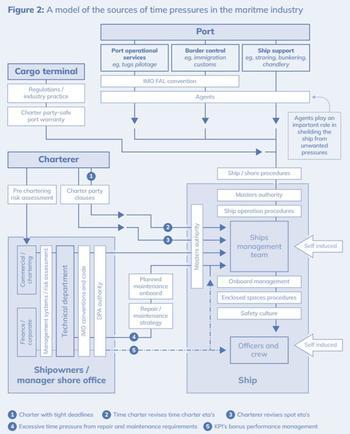

The resolution of demurrage claims is an everyday battleground for ship owner and charterer alike, although this tends to affect tramp operations – particularly dry bulk - more than liner operations. For the dry bulk trades, port and/or terminal time pressure is recognized by IMO as a significant risk factor.

The Bulk Load Unload (BLU) Manual requires, among other things, that ship and terminal management agree a load/unload plan, with timings, prior to commencing cargo operations.

Given the ever-present demand to increase port/terminal cargo throughput, particularly but not exclusively the handling of containers, time pressure has been cited as a causal factor for incidents involving a wider range of ship types. These include Ro-Ro loss of stability and loss of containers overboard following a failure to stow/secure in compliance with IMO standards.

This indicates there is not sufficient time to ensure cargo operations can be safely undertaken, and/or the that the ship is seaworthy prior to port departure.

Due to limitations on storage, tugs, pilots, channel tidal and navigation limits etc., any delay to a ship’s departure can rapidly escalate, causing potentially critical disruption to the ‘just in time’ supply chains that characterise logistics.

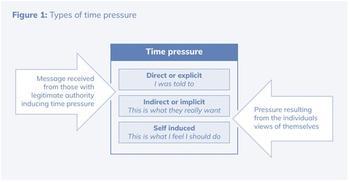

In the context of operations, therefore, demurrage may become a target to reduce which, within limits, is deemed acceptable. Beyond these limits, ships may be pressured to berth in marginal weather or directed to reduce their time on berth. In short, the 'design for operation' philosophy that informs port design is flawed as it is 'operating to design' with margins reducing over time. Much of the time pressure related to port operations may, consequently, be viewed as a means to the end of minimizing demurrage and/or CAPEX. In practice, this increased pressure/workload principally impacts ships’ crews. It shapes their behaviour and decision-making, crowding out essential safety-related tasks established in regulation and/or best practice, such as completion of a ship-shore checklist and other pre-arrival information exchange between ship and port/terminal staff. This may also impact the safety of shore-based personnel who board the ship in port.

Direct Time Pressure in Ports

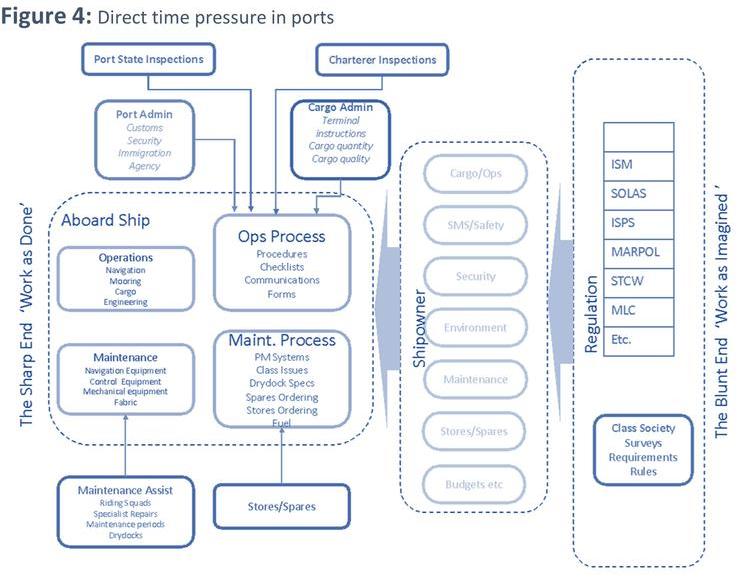

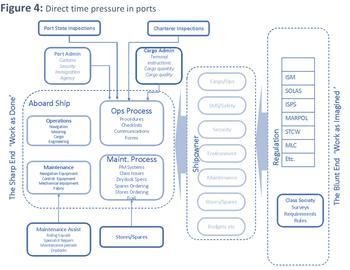

In port, pressure is exerted on a ship’s crew by a diverse range of stakeholders, each driven by their own agenda. A small army may descend on the ship demanding the immediate and undivided attention of senior staff (Figure 4).

Where to download the guide?

Figures and diagrams

Annex A

Further reading

Shipowner/Ship Manager Guide

Shipboard Guide